On the 72nd anniversary of the arrest of Ethel Rosenberg for allegedly providing valuable, top-secret information to the Russians about nuclear weapons designs, radar, sonar and jet propulsion engines, the WashingtonPost broke an explosive story headlined: “FBI searched Trump’s home to look for nuclear documents and other items, sources say.”

If true, the prospect of Trump selling highly classified nuclear documents to Vladimir Putin or the Saudis for billions of dollars and life-time asylum from US prosecution, adds an entirely new, and dangerous dimension, to the definition of Domestic Terrorism. Especially, if the terrorist conducting nuclear blackmail, is an angry, aggrieved, ex-President, entrusted with the most sensitive life and death secrets imaginable.

If the story was simply a “leak” by a patriotic FBI agent or DOJ employee intended to force Trump’s hand to release the detailed FBI affidavit revealing the crimes for which there was probable cause to search his home, Trump has been brilliantly outmaneuvered in an extraordinary high stakes game. In order to prove that he hadn’t commoditized nuclear secrets to our enemies—a crime punishable by life imprisonment or execution, as the Rosenberg’s learned–Trump would have no choice but to release the documents. Release of the sealed FBI search warrant, inventory documents and the affidavit—which can be like a lengthy indictment– threatens to strip bare the litany of crimes committed by Trump– serious enough to merit a court-ordered search of Mar-A-Lago. It’s a lose/lose situation for Trump.

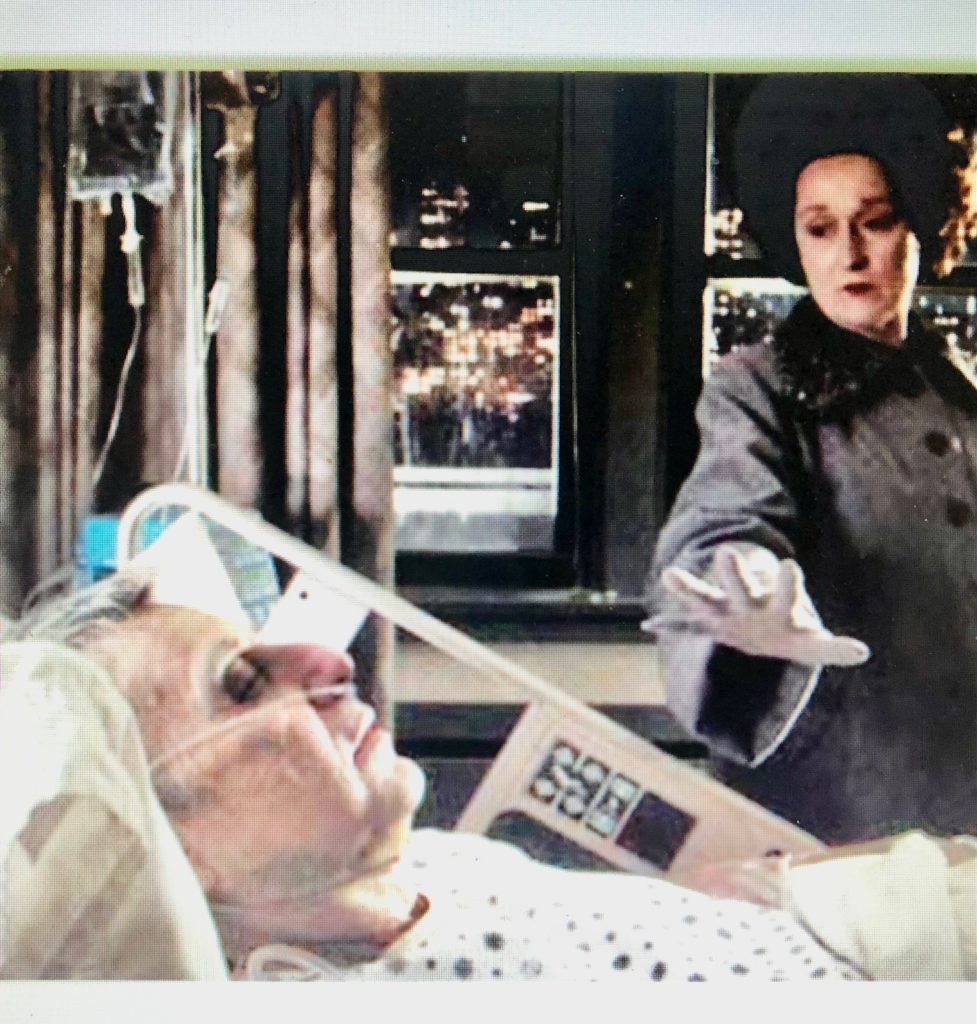

I devoured this five-alarm story from every media source I could find, when visions of Ethel Rosenberg, played by Meryl Streep in the HBO production of Tony Kushner’s Angels in America, began dancing on my brain. Quickly, I ran to get my printed copy of Kushner’s Pulitzer Prize winning play.

I turned to the page where the ghost of Ethel Rosenberg shows up at Roy Cohn’s bedside, as he lay dying of AIDS. Cohn, who 20 years later would become Donald Trump’s personal attorney, had hounded Ethel and her husband Julius into electric-chair executions three years after her arrest .

ETHEL: They won, Roy. You’re not a lawyer anymore.

ROY: But am I dead?

ETHEL: No. They beat you. You lost.

(Pause)

ETHEL:

I decided to come here so I could see if I could forgive you. You who I have hated so terribly. I have borne my hatred for you up into the heavens and made a needlesharp little star in the sky out of it. It’s the star of Ethel Rosenberg’s Hatred, and it burns every year for one night only, June 19. (June 19, 1953, was the day Ethel and her husband Julius were executed. Ethel had to be electrocuted three times before she finally died.) It burns acid green.

I came to forgive, but all I can do is take pleasure in your misery. Hoping I’d get to see you die more terrible than I did. And you are, ‘cause you’re dying in shit, Roy, defeated. And you could kill me, but you could never defeat me. You never won. And when you die all anyone will say is: better he had never lived at all.”

We know from decades of evidence going back 50 years, when Trump and Roy Cohn blocked Black families from moving into federally funded Trump-owned apartments in Brooklyn, that the ex-President is capable of unencumbered evil, as he proved again and again, with his calls for the death of the ultimately innocent Central Park Five, the fabrications over Barack Obama’s birth certificate and Mexicans storming the border, and the continuing Big Lie about the 2020 Election, and the incitement of people to violence on his behalf.

The only President in all of American history to be twice impeached, Trump’s recklessness, and disregard for any order but his, and his breathtaking lawbreaking have surprised even those of us who have long pegged him as a criminal cipher and a con, and a mob-boss wannabe.

Now, a calm, fearless Attorney General who brought the Oklahoma City Bomber to justice a generation ago, and lost family members to the lawlessness of Nazi Germany, has shown the world, that another totalitarian emperor has no clothes, and no where left to hide.

Maybe, the only eulogy that could be given for Trump’s 50-year temper tantrum in the public eye, is a variation on the theme expressed by the ghost of Ethel Rosenberg, over Roy Cohn’s deathbed: “Better he never had never lived a public life at all.”