I always have. I see him for the low-self esteem, self-hating, gun-posing runt that he is and has always been.

Feb 02, 2026

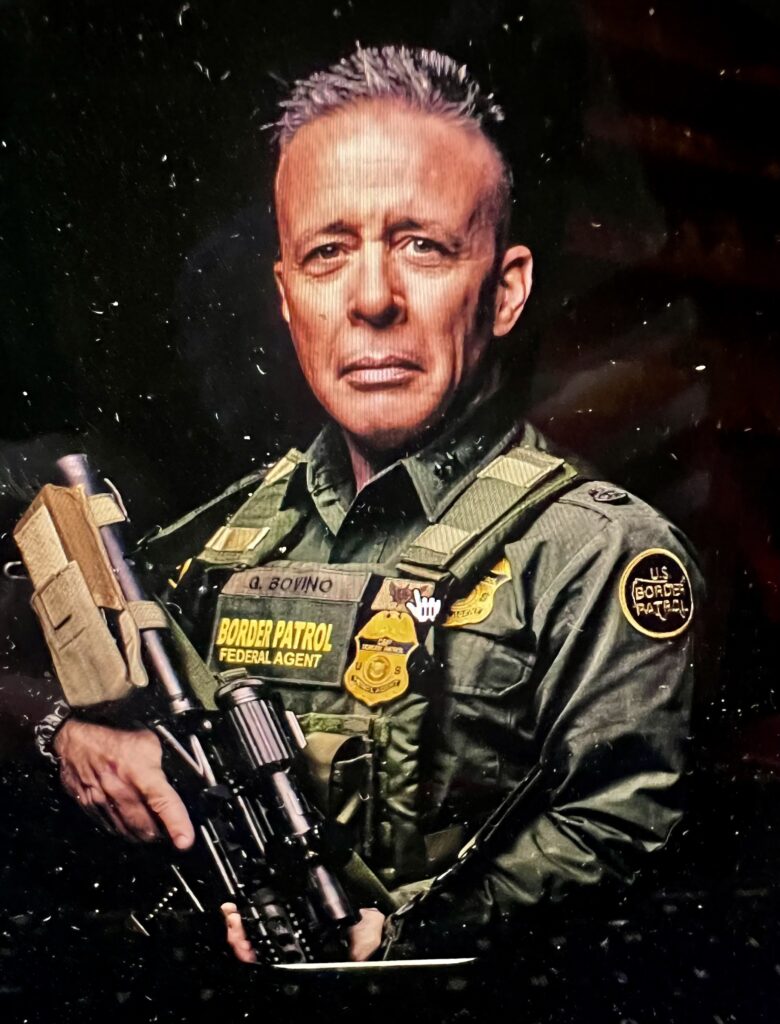

((Gregory Bovino’s HS graduation photo, 1988; Gun-toting Greg Bovino’s Instagram photo)

I know Greg Bovino.

From the days of the boys in our Italian ghetto,

When we played imaginary games like “hide the stiletto,”

Or, jumped on each others backs in “Johnnie Rides-the-Pony,”

I knew guys like Greg Bovino. Such a phoney.

“Buck, Buck, How many people can we fuck up?”

The saddest, most sadistic, shortest among us,

Would make the most noise, to get a laugh from the other boys,

Shielding themselves from getting sussed. . .

Yep, I know Greg Bovino.

A runt of a kid in a North Carolina hill country high school, who tried out for the wrestling team to look tough, but instead came off the fool.

Beaten down by his alcoholic father, tiny Greg Bovino was 11 years old when his father killed a 26-year old woman, crushing her with his truck. No bother.

“I was dead drunk,” Michael Bovino told the Charlotte Observer (NC), in 1981, and his 18-month prison sentence was reduced to 4 when he pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor of “death by motor vehicle,” nothing more.

“I’ve got a dead woman on my hands,” Michael Bovino said to anyone who would listen at the time. His son Greg, did’t want to hear it, for fear of becoming just like his father, which he did, despite his frantic attempts to bury his old man and that sorry past, the “dead woman on his hands,” reared her head, haunting him as best she could, in the person of Renee Nicole Good. And, little Greg, running in circles as fast from his father’s fate as he could, perversely accused that Good human of using her vehicle as a weapon, just like his father used his truck 45 years earlier, to commit “death by motor vehicle.” Some lessons never leave the mind of an 11-year old boy.

Too bad Greg Bovino didn’t learn a lesson from his father’s depraved indifference to human life, which ended up getting Michael Bovino imprisoned and then divorced from his hill country wife, when little Gregory Kent Bovino was only 14.

I know Greg Bovino.

I’ve seen him all my life, growing up in Italian enclaves of tiny little men with shriveled souls acting tough to strut and preen for the self-esteem they knew they lacked and feverishly hiding their heritage, of which they were ashamed.

His ancestors, like mine, were immigrants from Italy, and unlike mine, took 15 years to file their papers for citizenship, forced to do so after the virulent anti-Italian, anti-immigrant law of 1924, written by the KKK, the Stephen Miller of today.

Bovino’s blood line came from Calabria, Sicily, where Italians were not considered “white enough,” because their sun-drenched dark skin made them suspect on sight—like Mexicans, Puerto Ricans or Blacks—day or night, by the MAGA Supremacist Vampires of that time, and of today, all White.

But, I’m not the only one who can spot the screaming, self-hate that lurks under that faux SS Officer’s coat, taller than Bovino, which he wears as his talisman of inhumanity and sadism, which he’s vowed to once again, make great.

The Director of Academic Programs at the Calandra Italian/American Institute at the City University of NY, Joseph Sciorra, told the Chicago Sun Times, back in December, when tiny Greg Bovino, hiding in his oversized trench coat, was terrorizing Chicago’s immigrant families that it was astonishing that “a person whose grandfather was an immigrant was engaging in such abhorrent and violent treatment of contemporary migrants.”

Yes, I know Greg Bovino, and know that his self-hatred translated into beating migrants, kidnapping kids from the driveways of their homes, and having a “dead woman on his hands” —-just like his father—as well as a few dead men.

Like an addict getting high on his hits, each assault Bovino ordered was meant for his drunken father, who defied his wife’s admonition to “stay off the sauce,” guzzling down a few six-packs of beer, and murdering by vehicle, a young woman, and killing, as well, the early dreams of little Gregory Bovino’s life when he was 11 years old, forcing the underdeveloped child’s mind to fashion new fantasies of himself. And, so he did.

So, that very same year, 1981, little Greg escaped by discovering the Jack Nicholson movie, The Border, which was all about corrupt Border Patrol Agents who made money from a human-trafficking ring operating out of El Paso—a place where Bovino would later serve as a Border Patrol Agent, as if, in his narcissistic, immature mind, his life became a movie script. That movie influenced his life’s choice of an occupation; it’s too bad Bovino didn’t beef-up on his learning about his Italian immigrant ancestors and how they were brutalized for being different, not being “White enough”, and not speaking the language. But, his murderous, drunken and divorced father was dead to him, and the Italian immigrant part of his family history—his father’s story— had to be erased.

Instead, if Bovino had the slightest interest in the human story of immigrants, he might have learned of the historically important 11 Italian immigrants—all from Sicily, where his ancestors originated—with names like Joseph Macheca, Antonio Marchesi, James Caruso, Rocco Geraci, Frank Romero, and Charles Traina—tortured by White Supremacists for being different. Michele (later Michael Bovino), his great grandfather, was another Sicilian immigrant who came to American for a better life, in 1909, only 18 years after the massacre of 11 innocent Immigrants in New Orleans. It would be another 18 years, in 1927, when Bovino’s great-grandfather became a naturalized US citizen, the same year Italian immigrants Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, were executed for a crime they did not commit. The history of brutality against Italian immigrants in the America was intertwined with the history of immigrants in the Bovino family, but nothing stuck with little Greg.

Later in his career as he rose in the ranks of Border Patrol, Bovino had a professional duty to learn New Orleans’ history of anti-immigrant violence when he was made Chief of the Border Patrol Sector of New Orleans. Instead, Bovino decided not to educate himself, but to elevate his alter-ego, by posing in military drag all over social media. For the tiny man with the fey little voice, it was another chance to pose with guns, and tough guys, and appear bigger than his 64 angry inches. The only history of immigration Bovino knew, was being made up daily by the sadist Stephen Miller and guided by the Jim Crow laws of 30 states, just as Nazi lawyers used those laws—and the racially discriminatory US Immigration Act of 1924—when they drafted their Nuremberg Laws against Jews.

Bovino simply didn’t care, or he might have learned that these 11 innocent hardworking Italian immigrants, who spoke no English, and were unjustly accused of killing a New Orleans police captain—a murder planned and executed by the White Citizens Council running the City in 1891.

Had Bovino not been shopping for Nazi paraphernalia online, he might have learned that these 11 innocent Italian immigrants were jailed for their own safety after their full jury trial—by an all White jury—exonerated them. Despite their official “protection”, these 11 innocent Italian immigrants were pulled from the New Orleans prison by a mob of some 20,000 armed White Supremacists—like the ones who stormed the US Capitol on January 6, 2021—who beat, kicked, tortured and hanged them, and then shot the 11 innocent Italian immigrants repeatedly, in one of this country’s most deranged, inhumane and lawless campaigns of anti-immigrant violence, until the recent actions of Bovino, Miller, Noem, Honan, Trump and ICE in the second Trump Administration.

But, I know Greg Bovino, and have seen the kind of self-hate that drives him.

Little Greg would allow nothing to interfere with his personal vendetta against his Sicilian father’s blood, or his own rock-bottom low personal esteem, growing up in a town called, prophetically, Blowing Rock, North Carolina. Bovino’s swagger, self aggrandizement and seething self-importance, were all costume jewelry, designed to hide who he was.

I grew up with lots of Greg Bovinos, pygmy-like, morally-stunted people who picked on anyone’s differences to try to make others smaller than they were. But that never worked, no matter how many times they tried or lied. Diminishing others just never made them grow.

Bovino tried lying his way past Chicago area Federal Judge Sarah Ellis, who caught him, finding that the Federal Official lied to her in her courtroom when he claimed to have been “hit in the head by a rock” by an immigrant, to justify his use of excessive force. Bovino still had Blowing Rock on his brain, not rocks hitting his head.

If that was Bovino’s 11-year old’s interpretation of becoming a better Border Patrol agent inspired by the movie The Border 45 years earlier, it amounted to nothing more than the never-ending Bovino Border Bloviation of lies, fabrications and make believe. So many words, so little meaning; a perfect Trump Administration team player.

After a life-time of lying to himself, it was child’s play for Bovino to lie as he breathed about the excessive violence he and his BP team used in Kern County, California in their “Operation Return to Sender,” in early 2025, which amounted to his audition for a prime time appearance in the Trump Horror Show of Human Rights Violations.

Again, Bovino was called out on his lawless, tough-guy tactics by California AG Rob Bonta, along with 17 other State’s Attorney Generals, in a legal filing on December 31, 2025:

“The unscrupulous tactics used by Border Patrol Commander Greg Bovino and his team of agents during raids in Kern County, Los Angeles and across the nation threaten basic civil liberties afforded to all who call this country home.”

So what if he lied and got caught? Bovino LOVED the attention, as all of the Greg Bovinos I’ve ever known do. Deep down they know they’ll always be small and the slightest whiff of attention puffs them up. In Greg Bovino’s case he craved it, since he knew that without such self-image inflation, he would always be struggling to see above the steering wheel of the truck his father drove when he killed an innocent woman, back in 1981—an indelible dress rehearsal for the killing of Renee Good on his command.

Just this past week, Bovino mocked the Jewish faith of the U.S. Attorney in Minnesota, Daniel N Rosen, an Orthodox Jew. As the New York Times reported in its’ January 31 story entitled “Bovino Is Acused of Mocking Prosecutor’s Judaism:

“According to several people with knowledge of the telephone conversation which took place on January 12, Mr. Bovino made derisive remarks about the faith of the U.S. Attorney in Minnesota, Daniel N. Rosen….Mr. Bovino used the term “Chosen People,” in a mocking way….. He also asked sarcastically whether Mr. Rosen understood that Orthodox Jewish Criminals don’t take weekends off…”

The Times went on to report that in an interview last month with an on-line news outlet, Jewish Insider, US Attorney Rosen explained what the motivation was for him to seek his current role, so he could combat:

“the rapid escalation of violent anti-Semitism in the United States. Jewish history tells us that Jews fare poorly in societies that turn polarized, and where that polarization evolves into factional hatreds in the non-Jewish societies in which we live.”

Silent throughout Bovino’s and ICE’s terrorizing of immigrants around the country, is Jonathan Greenblatt, CEO of the Anti-Defamation League. Doesn’t the ADL know anti-Semitism when it sees it? Will they finally go after Greg Bovino, the way they went after Ivy League schools for allegedly allowing anti-Semitism on campus?

Who is more dangerous to Jews, a heavily armed, extreme right-wing government official with enormous fire-power at his command, or a lone college student with a protest sign? Why do Greg Bovino, Tucker Carlson, Nick Fuentes, the Oath Keepers, the Three Percenters and the Heritage Foundation all escape ADL’s examination? Why aren’t smashed car windows—Bovino’s preferred method of grabbing people from their cars in violation of their basic constitutional rights—seen as the 2026 version of the rolling Kristallnachts that they are, aimed at terrorizing and intimidating innocent people?

Judges, Attorney-Generals, and even former co-workers are beginning to hold Bovino and his gang of ICE bullies accountable.

Bovino’s former co-worker, Jenn Budd, a Border Patrol Senior Agent for the San Diego area on the California/Mexico border Region, told the Chicago Sun Times this December, that :

“Bovino was the Liberace of the Border Patrol, with all of his flamboyant behavior and the camera crews that followed him.”

In her book Against the Wall: My Journey from Border Patrol Agent to Immigrant Rights Activist, (Heliotrope Books, NY, NY, June, 2022), Budd writes:

“The Border Patrol is like a cult, and we say we bleed green and we always protect each other. The majority of agents are people I characterize with very low self-esteem…They follow a pattern and practice of making false accusations against the people you just beat up.”

Jenn Budd knows Greg Bovino; she worked with him, and she’s not afraid to call him out on his illegal, unconstitutional, bullying, attention-seeking behavior, and to call out ICE and the Border Patrol for creating an above-the-law para-military force, and an “institutional culture of sexism, racism and corruption”.

Just the perfect place for the tiny little Greg Bovinos of the world to hang out and hide behind gun barrels bigger than many of their physical organs.

“Buck, Buck, how many people can we fuck up?”