When I saw the young, lithe, black Buffalo Bills’ athlete Damar Hamlin collapse on an NFL football field in Cincinnati this week, after being hit hard in the chest, I could not stop staring at the constant playback loop of Hamlin’s crumbling to the ground . My mind had witnessed this horror before.

I struggled to place it. Then, one of the most powerful pieces of writing I’ve ever encountered marched into my mind.

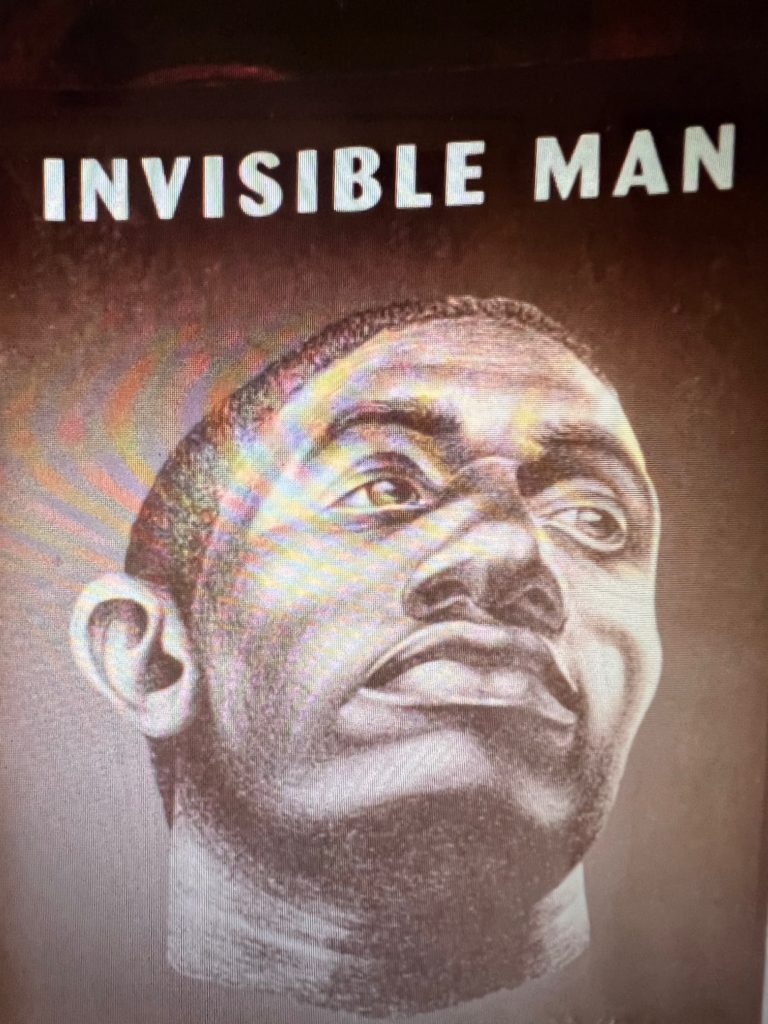

The brutal hit which stopped Hamlin’s heart reminded me of the chilling opening chapter of Ralph Ellison’s remarkable book “Invisible Man.” (Random House, NY, N.Y., 1952.)

In the riveting, cinematic descriptions which thrust readers head-first into his National Book Award winning work, Ellison chillingly depicted how wealthy White people looked right through young, athletic Black men, and saw only what they wanted to see, for whatever purpose they found gratifying or entertaining.

Again, I watched the replay of Hamlin falling backwards on a football field named Paycor—for a company that manages “human capital”– and thought of Ellison’s eloquent account, told through the eyes of a young, bright Black man invited into an elite gathering of southern, white, community leaders.

Ellison’s educated main Black character had earned a college scholarship, and to receive it, he was told by the Superintendent of Schools, he would have the privilege of giving a speech to a roomful of old, white, male movers and shakers.

They would be impressed by his eloquence, the young Black man was promised, but first, he and nine other young, well-built black men had to provide some pugilistic entertainment for the rich, powerful audience, of inebriated good ole’ boys:

“ All of the town’s big shots were there in their tuxedos, wolfing down buffet foods, drinking beer and whiskey and smoking black cigars. It was a large room with a high ceiling. Chairs were arranged in neat rows around three sides of a portable boxing ring. The fourth side was clear, revealing a gleaming space of polished floor.”

“In those pre-invisible days, I visualized myself as a potential Booker T. Washington…I suspected the fighting might detract from the dignity of my speech.

We were led out of the elevator through a rococo hall into an anteroom and told to get into our fighting togs. Each of us was issued a pair of boxing gloves and ushered into the big mirrored hall…”

“We were a small tight group, clustered together, our bare upper bodies touching and shining with anticipatory sweat, while up front the big shots were becoming increasingly excited… Suddenly, I heard the School Superintendent, who told me to come, yell, ‘Bring up the Shines, gentlemen! ‘Bring up the little Shines!”

Hit ‘em hard; bring ‘em down; that’s what we want! We pay them well enough to allow them to play this violent game we crave. They know what they are buying into. Look at how quickly we got the ambulance on the field! Cut to commercial!

“We were ordered to get into the ring…All 10 of us climbed under the ropes and allowed ourselves to be blindfolded, with broad bands of white cloth…I felt a sudden fit of blind terror …I stood against the ropes trembling… it seemed as if all nine of the boys had turned upon me at once. Blows pounded me from all sides…A glove connected with my head, filling my mouth with warm blood…”

“Everybody fought everybody else…I heard one boy scream in pain as he smashed his hand against a ring post…The (White) men kept yelling: ‘Slug him, black boy! Knock his guts out! Uppercut him! Kill him! Kill that big boy!’

When the bell sounded, two men in tuxedos leapt into the ring and removed the blindfolds…”

The White men — bankers, lawyers, judges, doctors, fire chiefs, teachers, merchants and pastors — all dressed in tuxedos, now arranged for the second act of the evening’s entertainment: two Black “boys” would fight it out, before all would get some money:

“I saw the howling of red faces crouching tense beneath the cloud of blue-grey smoke…I wanted to deliver my speech more than anything because I felt that only these men could judge truly my ability…A blow to my head as I danced about sent my right eye popping like a Jack-in-the-Box and settled my dilemma…I wondered if I would now be allowed to speak…”

The tuxedoed White men stopped the fight, but only because they wanted to see one more show—their own “Superbowl” of entertainment.

Ellison’s evil rich men rolled away the portable boxing ring, and set up a small square rug in the vacant space surrounded by chairs. An emcee gave the signal for the young, Black men to “come and get your money,” a collection of gold, coins and a few crumpled bills tossed in the middle of the rug.

I looked at the listless body of Damar Hamlin, laying on a NFL football field named for a company that dealt in “human capital”, and wondered if the gobs of money tossed his way was worth the price. But then, I knew what atrocities came next in “Invisible Man.” Unlike Hamlin, Ellison’s young black scholar-athlete was still conscious to narrate for us:

“As told, we got around the square rug on our knees. ‘Ready, Go!’ the emcee said. I lunged for a yellow coin lying on a blue design of the carpet, touching it …A hot, violent force tore through my body, shaking me like a wet rat. The rug was electrified…my muscles jumped, my nerves jangled, writhed…Suddenly, I saw a boy lifted in the air, glistening with sweat like a circus seal, and dropped, his wet back landing flush upon the charged rug, heard him yell, and saw him literally dance upon his back, his elbows beating a frenzied tattoo upon the floor, his muscles twitching like the flesh of a horse stung by too many flies… his face was gray and no one stopped him when he ran from the floor, amid booming laughter.”

To their credit, the well-heeled crowd at the Cincinnati Bengal’s NFL stadium didn’t cheer, but, instead, were stunned into silence by the consequences of the brutality they witnessed, and the other entertainers were brought to tears.

Ellison’s journey for his eloquent Black hero was different. To ground himself against the pre-meditated electric shock, the young, college-bound Black man, grabbed the wooden leg of a chair being straddled by a laughing, beer-bellied, drunken White man and tried to topple his tormentor onto the electrified carpet. The fat, rich, White man kicked him viciously in the chest and back onto the charged rug. He was fortunate the blow to his chest didn’t send him into cardiac arrest:

“ The chair flew out of my hand, and I felt myself going… It was as though I had rolled through a bed of hot coals. It seemed a whole century would pass before I would roll free, a century in which I was seared through the deepest levels of my body to the fearful breath within me, and the breath seared and heated to the point of explosion. It’ll all be over in a flash, I thought… It’ll all be over in a flash.”

Did anybody die? Not this time, not that we know…But wattabout that game?