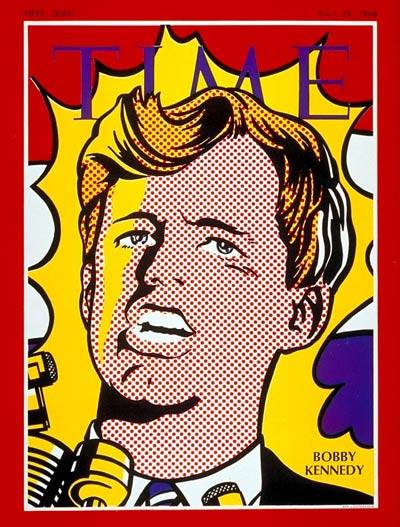

On the 50th Anniversary of Robert F. Kennedy’s assassination, my mind has been replaying the first moment I met him. It was 1964, the year after his brother was murdered, and he was campaigning for the U.S. Senate seat from New York State. I was 15 years old, and RFK was visiting Sunset City Shopping Center in North Babylon, L.I., just a few miles from where I grew up.

Since my mother and father were among the few registered Democrats in a working-class enclave of Republicans, the local Democratic Committeeman, Chester Clarke, asked me if I’d like to “meet Bobby” when he came to town. I jumped at the chance, and spent days painting the words “HELLO, BOBBY!” on an old bed sheet my mother gave me.

On the day of RFK’s visit, Chet Clarke drove me to the rally and placed me directly behind the rope, where I’d be able to shake Bobby’s hand, and my huge “Hello, Bobby!” banner would be front and center. After the RFK cheerleaders sang “Robert Kennedy, Vote on November 3, There’s Gonna Be a Great Day,” (to the tune of “When You’re Down & Out, Lift Up Your Head and Shout,”) and Bobby gave a short, stirring speech, the candidate began to make his way around the rope, shaking hands.

He started across from me and I couldn’t take my eyes off of the bird-thin legs of Dorothy Kilgallen, the Talk Show host and journalist, walking right next to him. Her legs were so thin that her stockings flapped in the wind, as did Bobby’s wild, wispy hair.

When he worked his way around the rope to me, he put his hand on my shoulder, and said: “That’s quite a sign you’ve got there! Thank you!”, and he continued around the rope to shake every hand.

As he was leaving, there was a scuffle a few feet behind me. An obnoxious kid from my high school–the only person I’ve ever punched in the face–was pulled down from a light pole by Suffolk County police for pointing a plastic water pistol at RFK.

In the early morning hours of June 6, 1968, when Bobby was shot and killed in Los Angeles by a real pistol, I was driving past Sunset City Shopping Center in North Babylon, taking my father to the Babylon Train Station to catch a 5:30 am train into NYC to his job as a building maintenance man. We turned on the all-news radio station to hear the late night baseball scores from the West Coast, but the only news we heard on the radio was that RFK was shot and killed. I dropped my father off at the LIRR Station, drove back to the spot where RFK touched my shoulder four-years earlier, shut off the car, and cried uncontrollably.

In the early morning hours of June 6, 1968, when Bobby was shot and killed in Los Angeles by a real pistol, I was driving past Sunset City Shopping Center in North Babylon, taking my father to the Babylon Train Station to catch a 5:30 am train into NYC to his job as a building maintenance man. We turned on the all-news radio station to hear the late night baseball scores from the West Coast, but the only news we heard on the radio was that RFK was shot and killed. I dropped my father off at the LIRR Station, drove back to the spot where RFK touched my shoulder four-years earlier, shut off the car, and cried uncontrollably.

The following day, Robert F. Kennedy’s dead body would be flown back to New York to St. Patrick’s Cathedral for a public funeral which tens of thousands of people would attend. Intuitively, I knew I had to be there, to feel this loss as deeply as I could and never permit anything to turn me back toward a life of quiet desperation, nor to be numbed into inaction by my own deep sorrow.

I got up early with my father on the first day Kennedy’s body was laid-in-state at St. Patrick’s. We stopped at the newspaper kiosk at the Babylon train station’s lower level, picked up a copy of the New York Daily News for him, and the New York Times for me. We boarded his regular early morning train that was already waiting at the station. Both newspapers predicted huge crowds of mourners would jam Manhattan that day. .

When we got into the City, I started walking uptown to the Cathedral, and, blocks before I reached the church, I noticed the lines, stretching in all directions. It was still early, 6:45 in the morning, and the closest point I could join the line was at 45th Street and 5th Avenue, some five blocks from the main entrance to St. Patrick’s.

People were dressed in all kinds of clothing, but I focused on a small group of older Black women dressed up like it was Easter Sunday, wearing pastel-colored suits and pillbox hats with fine lacey black veils pinned over the front part of their hats, ready to be draped over their eyes when they entered the sanctuary.

I studied these elderly and elegant Black women carefully, picturing them praying together two months earlier when they learned Martin Luther King, Jr., was killed. I saw them standing in their church somewhere Uptown or in Brooklyn or out on Long Island in Roosevelt, in the same bright pastel-colored suits and pillbox hats, with their fine lacey black veils pulled down over their eyes, unable to hold back their tears. We moved agonizingly slowly, and as the heat of the day caused me to perspire under my sport jacket, I marveled at how the older Black ladies looked as cool and calm as the moment they joined the line hours ago. They had been through this before.

When we finally reached the cool vestibule of the Cathedral, and moved slowly up the center aisle, I stood on my toes, craning my neck to get a glimpse of RFK’s coffin, at the foot of the grey stone altar rail. On the pillars in front of the main altar, I noticed a large statue of St. Patrick, carved carefully in stone, with a long flowing beard and a glowering look aimed at any communicant who would dare to sin before the eyes of an angry God.

The line shifted a bit and I could clearly see Robert Kennedy’s coffin, . Directly behind the casket, standing erect, hands falling stiffly by his side, eyes staring straight ahead, was Jack Paar, the television talk show host, a close friend of the Kennedy family. Flash bulbs went off, and I shot an angry look at a few idiots with instamatic cameras who saw this as simply the latest tourist attraction in New York. I wanted the statue of St. Patrick to strike them down or at least, turn them to stone. I took a few steps forward and stopped. In front of the coffin, less than 10 feet away from me, stood a young boy not more than 14 years old, just 5 years younger than I. His facial muscles quivered and his hands were clasped tightly in front of him as he fought back tears. It was Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., and the sight of RFK’s son, so fragile and alone, overwhelmed me with grief. I wanted to jump out of line and hug this frail child and apologize for what hate, fear and gun violence had done to his father.

I genuflected on one knee , under the stony glare of St. Patrick, in the bright morning light filtering through the Cathedral’s stained glass, and there, before the tomb of the man who inspired me to do good and the young son robbed of his father’s warm smile and comforting embrace, I vowed to become, as Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., suggested, “dangerously unselfish” and dedicate myself to life, and love, and public service.