My brother Michael would have been 75 years old this week, and he has been on my mind a lot lately.

Somehow, I think my 6-year old granddaughter must have known that. At dinner on the night before my brother’s birthday, I was telling a make-believe story about “Peter, Peter Pasta Eater,” and another boy. My granddaughters, ages 6 & 4 love hearing my made-on-the spot stories the way my brother’s oldest daughter and son did, when they were the same ages. And, I love telling them, vamping along the way, watching their eyes grow as big as pizza pies, suspense building.

I was searching for the name of the other boy in the story, when my granddaughter asked me for it, and “Michael” was the first name that popped into my mind, and came from my mouth.

“Wait,” my oldest granddaughter said, stopping the story cold. “Is this real or is it a make-believe story?”

“It’s a make-believe story,” I said, surprised by her question. “Why do you ask?”

“Well,” she said, looking at me with her saucer-sized eyes, “isn’t Michael one of your brothers’ names?

I was stunned. Was she reading my mind? My face? Were my emotions that evident to this sweet, sensitive child?

“Why, yes—yes it is,” I said. And, before I could correct myself and say, “yes, it was,” the story moved on, and my granddaughters wanted to know how it ended. On the eve of what would have been my brother’s 75th birthday, his name found it’s way into a story I was creating for the two human beings who are everything to me.

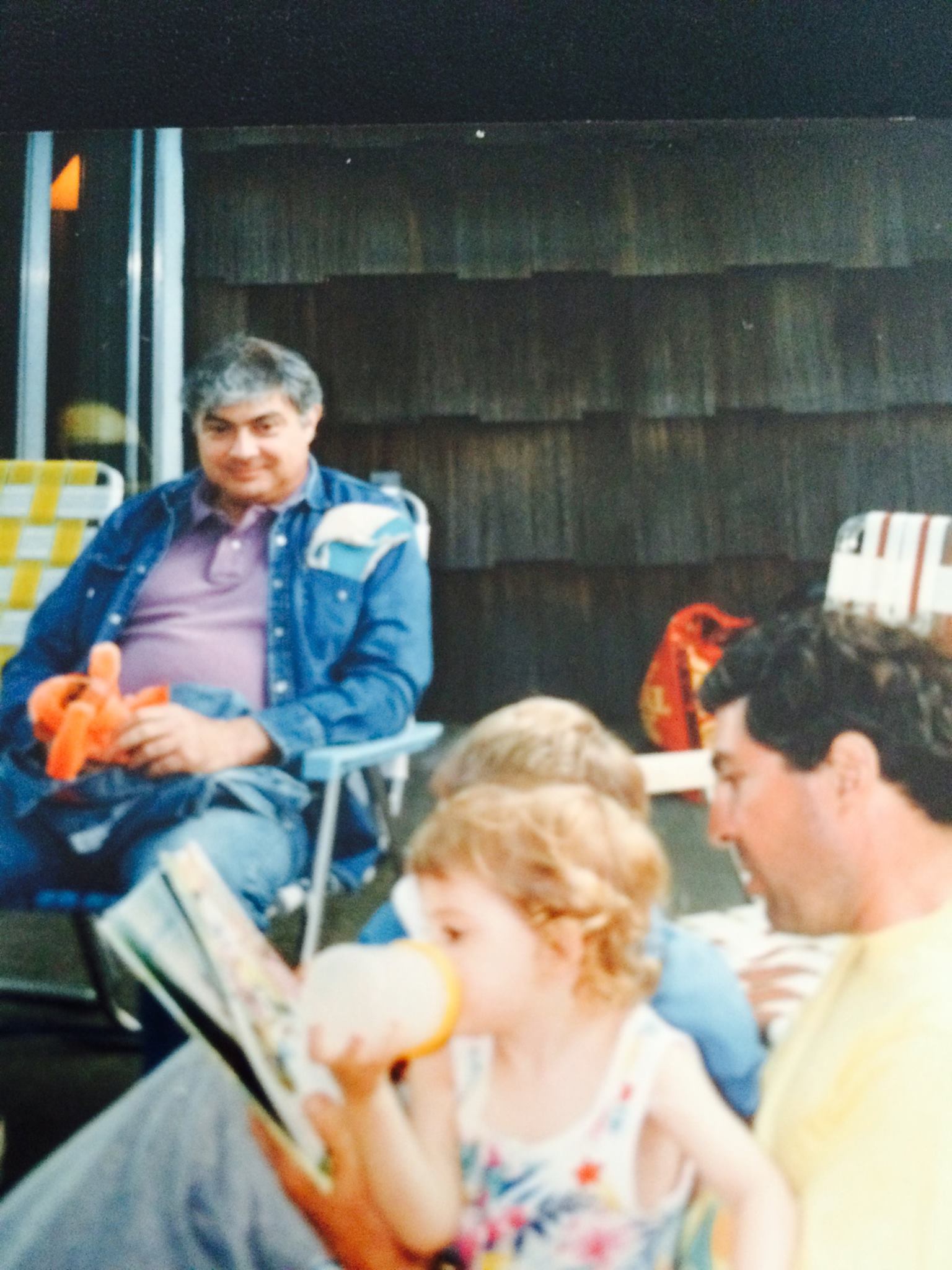

It got me thinking of how my brother would have smiled warmly, quietly at my granddaughters, the way he glowed softly as I watched him observe each one of his four children when they were babies, and the world was still fresh and innocent.

My brother Michael was my first hero, a calm gentle presence in my chaotic early life, the opposite of my father whose temper could explode as quickly as the steam boilers he worked on all his life. Gifted with patience, my brother would assemble all of my toys that my father had no patience for putting together.

My first real visual memory of my brother was through the split front seat of a 1958 Ford Fairlane, when I was 10 or 11 years old. He had taken me to a drive-in movie one night, along with his girl friend, who later became his wife. They sat in the back seat; I sat in the front. I was curious about what my brother was doing back there. But, fatigue conquered my curiosity, and I fell asleep while I tried to sneak a peak of a show that I was convinced was more fascinating than the movie on the big screen in front of me. My brother, nine-years older than I, carried me back into my parents house and up to my bedroom that night, and, for years, laughed gently at my invasion of his privacy.

I always saw my brother through my mother’s eyes, and that view was rose-colored, gentle and perfect, even when my brother’s life took on a far different, more tumultuous tone in later years.

To my mother, to me, my brother was always there, ready to help, to calm the waters. He could build anything—a four-poster bed, a bicycle, a house. I once watched him cook a meal from scratch for two dozen people, each ingredient carefully chosen, each choice delicately considered, each course, better than the one before. I was mesmerized by his short, stubby fingers and how much they looked like our mother’s.

My brother’s life and mine, diverged sharply over the years, and my idolization of him turned into sadness, anger, sorrow and then, in the end, love again. Whatever he did, and he did plenty, he was always my mother’s son, and early in his life, the very model of how I believed a man, and father, should behave.

To my granddaughter, who never met him, Michael was my brother. He was real, not make believe.