To be in the presence of Bill Ayres, former Catholic priest and co-founder of WHY Hunger with Harry Chapin, is to be bathed in the warm glow of hope and love.

During this week that we celebrate, and try to replicate in some small way, the life and actions of Dr. Martin Luther King, Bill Ayres’ life gives us some practical instructions of just how to do it.

As with Dr. King, the driving forces of Bill Ayres’ activism are his faith, and his love of the dignity of all human beings. It’s what’s guided Bill’s life for some six decades—in addition to a unique sense of how music can change individual lives, and through it, the world. With the Grammy Awards less than three weeks away, it’s important to note the increasing urgency of intertwining the works of artists with social action, the way Harry Chapin did during the final decade of his brief life.

Our Bill Ayres of Huntington Station, NY, whom I know and love–the real Bill Ayres, as I call him, so he cannot be confused with the Chicago-area, headline-grabbing, violence-winking, Weather Underground’s Bill Ayers —is the real, long-term radical social activist. His indefatigable efforts fighting hunger and poverty continue to make a difference in thousands of lives each day. Beyond his remarkable work fighting hunger, poverty and food insecurity with singer/songwriter Harry Chapin, and the Chapin family over the past 5 decades, Bill Ayres’ own life and work is the stuff of inspiration.

That’s why it’s fitting that Huntington’s Bill Ayres—our Bill Ayres– shares a birthday with long-time Civil Rights leader, Julian Bond, on the day before Dr. Martin Luther King’s birthday. Not only did both men march and work with Dr. King, but they devoted most of their lives to practicing the kind of targeted, effective, never-ending non-violence which Martin Luther King preached. Our Bill Ayres— and Julian Bond–personify the very best in service to others, which Martin Luther King Day has come to represent.

Both became aware of the continuing struggle for civil and human rights in this country at roughly the same time. Bond co-founded the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) while a student at all-Black Morehouse College in 1960, where he first met Dr. King. He risked his life registering new voters during Freedom Summer in Mississippi, in 1964. Ayres, entered the seminary to study the priesthood, in 1963—not to escape the troubled world, but to embrace and repair it, influenced by the teachings of Catholic progressives like Dorothy Day and Thomas Merton.

In 1966—the same year Bill Ayres entered the priesthood–the overwhelmingly white, male Georgia House of Representatives refused to seat Julian Bond —despite his being elected to represent his Georgia Legislative district—Martin Luther King came and preached against the illegal and racist action of the Georgia Legislature, and organized a march in support of Julian Bond’s right to serve. Five years later, Bond co-founded the Southern Poverty Law Center, a leading civil rights organization, which continues to be a strong voice against discrimination and hate to this day, nearly a decade after Bond’s death at the age of 75, in 2015.

Bill Ayres, our Bill Ayers, would be the last person to encourage any comparison between his tireless efforts battling hunger, poverty and powerlessness, with the work of Julian Bond, or, especially of Dr. King. Regardless of Bill’s self-effacing modesty, the similarities are there for all to see.

Just after the 50th Anniversary of the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, I interviewed our Bill Ayres, in the New York City headquarters of WHYHunger, and in the tranquil beauty of his beloved Heckscher Park in the Village of Huntington, L.I., not far from his home. We peacefully strolled around the Park’s calm lake, when I asked him about the influence of Dr. King on his life’s work:

“In 1963, I was in the March on Washington, I was a kid, in the seminary. Then I marched with him lots of times, heard him preach in the church, read all his stuff, and, I knew that racism was an evil; poverty was an evil and that they were all very much connected…”

Bill Ayres attended the Immaculate Conception seminary in Huntington for six years in the early 1960’s where he began reading Dr. King’s “stuff”, as he described it.

“The inspiration for me in all of this is, of course, the social teachings of the church and the Gospel of Matthew, and lots of other places. King is kind of the one who put that into action. Paulo Freire, a Brazilian educator driven out of after a military coup in 1964, wound up in Boston College and taught with a friend of mine up there and at UN. I met him a few times and heard him speak. He had this whole thing that the root cause of hunger is poverty and the root cause of poverty is powerlessness—I repeated this mantra to Harry Chapin a couple of times when I first met him. That’s always been our theme.”

We stopped walking as Bill’s kind, gentle-blue eyes, underscored that point:

“It’s the powerlessness that comes from on top, from oppression; racial oppression, sexual and, economic injustice. That’s where we came from and that’s where we’ve always been.

Serving Catholic parishes in conservative Long Island towns like Babylon and Seaford, Father Bill Ayres, did not look the part of the “radical priest,” despite, his deep, Catholic Worker beliefs. I asked him if he ever met the Berrigans, the “radical priests” of the 1960’s, arrested on many occasions for protesting the War in Vietnam, and destroying draft board records, as depicted in the recent TV series “Fellow Travelers.”

“Interesting. I met them, but didn’t know them. After I was ordained there was a priest friend of mine, who was a friend of the Berrigans. And Berrigan invited him and me to meet Thomas Merton. I never got there. Berrigan couldn’t go and we cancelled the whole thing. It’s one of those missed opportunities. I was on marches with the Berrigans; I was part of the anti-war movement. I would have loved to have met Merton. His book, The Seven Storey Mountain, influenced me to become a priest. He was a convert; He was a big influence on lots of people including me. A remarkable man.”

Thomas Merton’s writings and teachings influenced not only Bill Ayres, but generations of progressive Catholic activists to move well beyond the fundamentalist strictures of the hierarchy of the Catholic Church establishment. In the recent TV series “Fellow Travelers,” one of the main characters “Skippy,”—played by the actor Jonathan Bailey—is a Catholic, social activist who opposed the church’s complicity in the War in Vietnam as well as its’ dogmatic positions against marriage and homosexuality, kept a copy of Merton’s The Seven Storey Mountain on his night table.

It was the Church’s unyielding restrictions against priests marrying that drove Bill Ayres from the organized priesthood. After 13 years of serving two Catholic parishes, Bill met and fell in love with his wife, Jeannine, to whom he’s still married 45 years later. But while, Ayres may have formally left the priesthood, his life of service to others never left him. His congregation grew to a national size when he met Harry Chapin by interviewing him on Ayres’ radio program “On The Rock,” in 1973.

Serendipitously, Chapin’s great-aunt through marriage was Dorothy Day, one of the heroic figures in Bill Ayres life:

“If You look on my desk, I have a picture of Dorothy Day. I used to go down to her gatherings on Friday night on Christopher Street. (In NYC) I was very influenced by Dorothy Day; she was one of my role models, radical Catholic, sort of who I am. Harry and I talked about her, “Well, you know, I’m related to her,” he said, “and he was proud of it”.

It was Bill Ayres who alerted me to the remarkable book by Day’s granddaughter Kate Hennessy, “Dorothy Day: The World Will Be Saved by Beauty,” which, in intimate and exquisite detail, illuminates the life that the revolutionary Catholic worker lived, and how much she accomplished for others. And it was Bill, ever the teacher and mentor, who took from his personal bookshelf, a the dog-eared, underlined, hard-copy of a book—a guide for social action, really—which meant a lot to him—and gifted it to me. It was his copy of Paulo Freire’s “Pedagogy of the Oppressed, “ a blueprint for honoring—and acting for– the humanity in all of us.

Bill Ayres’ all-encompassing humanity can leave you in quiet awe, and I was sure he must have had the same effect upon Harry Chapin, whom he met while still a practicing priest. I asked him if Harry believed in God:

“There’s an interesting thing here,” Ayres said. “ I’m a Catholic priest here and he’s this rock and roll guy. An interesting partnership. He loved it. He just thought it was a wild thing. He called me “Wild Bill” because I did all this crazy stuff. But he said to me, ‘you know, I’m not a believer; I come from a bunch of agnostics; I grew up in the Episcopal Church, I sang in the Episcopal Church. But I’m not really religious. ‘

“However, he evolved. And, part of the evolution was that he saw the goodness in the people who were running these food pantries and soup kitchens. And he had this great line, “I believe in the believers.”

“ Just a few months before Harry died, we were having this conversation about religion. He said , “I believe in God.” Big breakthrough. “But I don’t believe in a god of fear or vengeance. I believe in a god who loves people. I believe in a God that gives lots of hugs.” Harry liked to hug people. He and I talked about Jesus over the years. The whole thing is love and justice; it’s what’s it all about.”

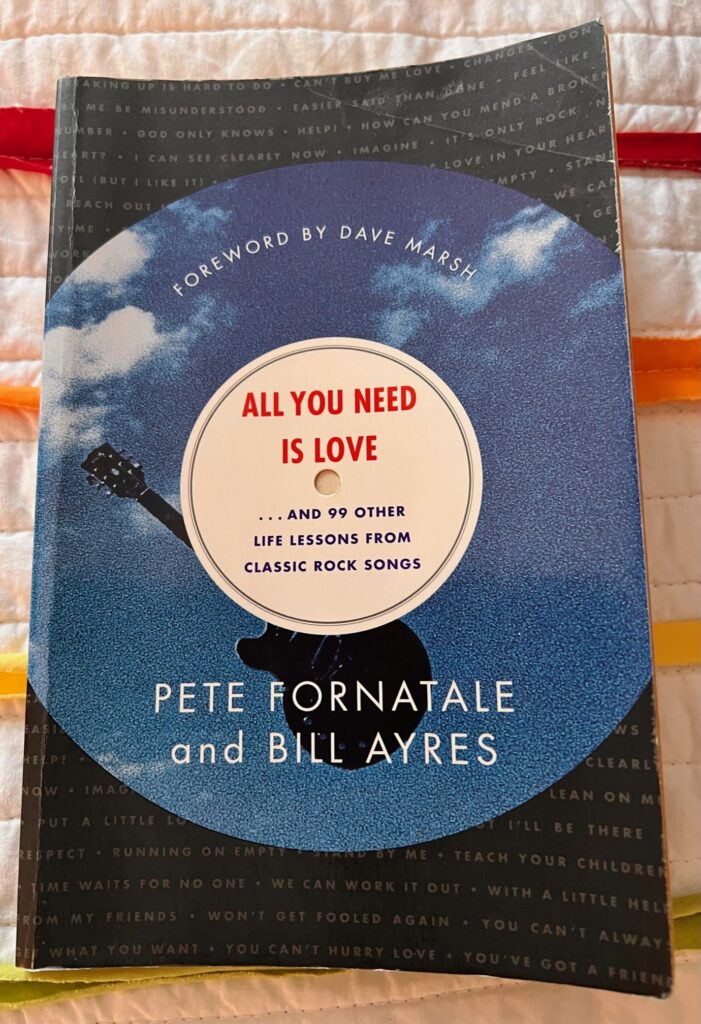

My favorite of Bill Ayres’ books, from which I seek inspiration, hope and guidance frequently, is his simple, soul-refreshing teaching tool which he wrote with his radio soul-mate, Pete Fornatale, entitled “All You Need Is Love..and 99 Other Life Lessons from Classic Rock Songs.” The book is dedicated to Harry Chapin, especially for Chapin’s use of his music, song and story-telling gifts to help “millions more to have food in their stomachs, dignity in their lives and hope in their spirits.”

It’s what our Bill Ayres has devoted a lifetime of service to doing, and still practices every single day. To me, it’s the perfect message, and model of behavior, for Martin Luther King Day, and for each love-filled moment of our lives.