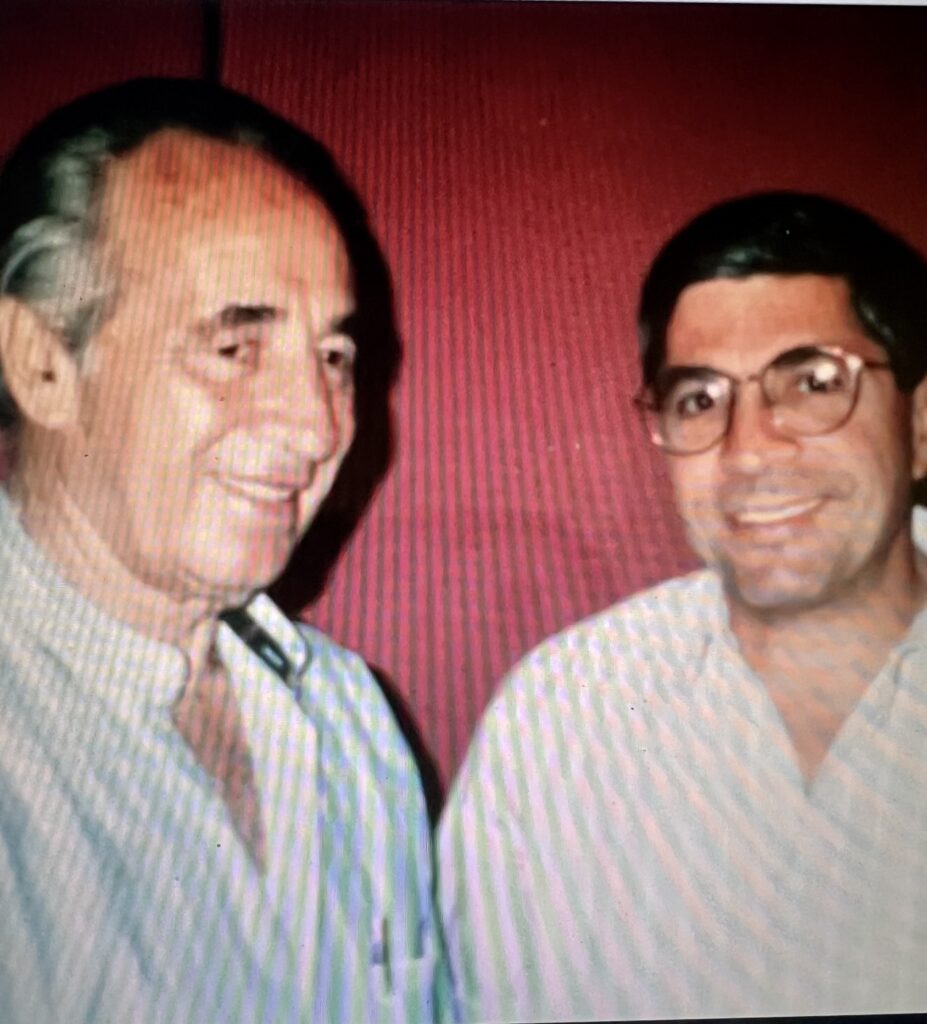

(Shimon Peres and me, Jerusalem, Israel, 1991.)

I have been haunted by two memories this week.

Memories which have come back to me as nightmares, blaring to me like air-raid sirens in the night, because they tried to warn us—some 30 years ago—of the mass murders which just occurred in Israel, the killing of civilians in Gaza, and the haunting spectre of a dark endless pit, carved out by hate and violence, into which thousands of innocent human beings would disappear.

If only we had listened and acted upon those warnings.

In one memory, the face and voice of Shimon Peres, former Israeli Prime Minister, President, Foreign Minister, and Nobel Peace Prize winner is right in front of mine. In the other, Yitzak Rabin, Israeli war hero, Prime Minister, and Nobel Peace Prize winner, shakes my hand, and repeats the word “Shalom” over and over and over again.

I first met Shimon Peres 32 years ago this summer, as part of a small group of public officials on a fact-finding mission to Israel, sponsored by New York’s Jewish Community Relations Council. Peres, then Chairman of the out-of-power Israeli Labour Party and a member of the Israeli Knesset, talked passionately with us about peace and democracy for nearly an hour.

He had devoted his life to the pursuit of both, first as a fighter in Israel’sHaganah—under the direction of his mentor David Ben-Gurion—when the nation was formed in 1948; then, two-years after our meeting, Peres was a signatory to the Oslo Accords for peace with the Palestinian Liberation Organization, along with Yasir Arafat, Israeli Prime Minister Yitzak Rabin, and U.S. President Bill Clinton.

Speaking freely on the day before Mikhail Gorbachev returned to power during a tumultuous time in the Soviet Union, Peres talked of history happening as we spoke, not far from the classroom where me met, in Jerusalem.

I asked Peres about the prospects for peace in the Middle East, since he was so closely identified with the effort to achieve it. He quickly outlined his plan for peace, and for Israel’s future:

“ The three basic problems in Israel’s future are: 1) We must achieve peace before the Middle East goes nuclear; 2) We must keep Israel from becoming a bi-national state. We may end up keeping the territories as Likud wants, but losing our country. What makes a country is not land, but people. We don’t want to dominate others. Who is a hero? The one who dominates himself.”

Shimon Perez, paused and stayed silent for a moment, to allow the vision he had for the Israel’s future, to sink it. He had been grappling with these matters for most of his lifetime, appointed by Ben-Gurion to be Israel’s first Navy Secretary at the age of twenty-four, in 1948, the year before I was born.

I stared at his face, following each deeply creased line, to see how far back in time I could trace his thoughts, and the beliefs that drove him.

“The third problem,” Perez said, “is economic. We cannot live forever on aid of the U.S. Right now, world markets are more important; dangers and opportunities are regional; we cannot solve our problems without reorganizing our water sources.”

Peres was preaching now, his soul on fire:

“We should combine the oil of the Saudis, with the water of Turkey and the know-how of Israel to build a common market. For us, the way the peace will wind up is more important than how it will be obtained. For us, it is a matter of life and death; the only option we have is to become a medical center for the region, a technological center for the region, what with the number of Soviet doctors and engineers coming to Israel. We shall have to give back the territories — they should be demilitarized. They would run their lives without our intervention, such as Gaza. Jerusalem would have to remain united. We have to work toward a regional economy with regional solutions…The motivation for the Palestinian conflict may disappear if it’s solved along the lines I have suggested.”

Peres’ bright eyes sparkled as he detailed his plan for peace throughout the region. He noted that Israel did not have territorial issues with Eqypt or Jordan, but only with Syria, over the Golan Heights, which, he noted, “was not a holy place.”

I asked Peres to suggest some alternatives for dealing with the Golan and Gaza.

“I’m not in the mood to enter into negotiations, “ Peres said. “When we start negotiations, then we’ll see. One day, Saddam Hussein will disappear. Our enemies are not the people, nor a religion. We must judge the land by its’ people. What is Gaza? For me, Gaza doesn’t belong to us; it belongs to the people who live there. I’d give back Gaza; I’d admit it is a fact of life — it is theirs. The same goes for the West Bank. We have to cut the geography in accordance with the demography. Both areas would have to be demilitarized.”

He finished answering our questions and Shimon Peres, dressed in an open-necked, short-sleeved sport shirt that matched mine, shook my hand and posed for photos. I told him I worked with New York Governor Mario Cuomo and his heavy, tired eyes, lifted at each corner.

“ Please give the Governor my warmest regards,” Peres told me.

The following year, 1992, I accompanied Cuomo on his first trip to Israel, watching as the Governor and Peres embraced like long lost brothers; marveling at how each resembled the other in voice, manner, gravitas and appearance. The deep lines in their faces seemed to be mirror images.

Peres had just lost a bruising leadership battle to lead Israel’s Labour Party, to Yitzhak Rabin, who went on to be elected Prime Minister in June of that year.

Rabin, who was the Israeli Army’s Chief of Staff during the 6-Day War of 1967, and a war hero, was the first native-born Israeli to be elected Prime Minister. As Prime Minister, Rabin immediately put a freeze on new Israeli settlements in the occupied territories, infuriating the opposition Likud Party, and the nation’s growing number of fundamentalist religious extremists on the Far Right.

At the suggestion of Peres, who was Rabin’s Foreign Minister, the newly elected leader of Israel met in his Jerusalem office with Cuomo, in September 1992.

Prime Minister Rabin, joined by his wife Leah, welcomed us into his office—a simple, straightforward office without ostentation, much like the man himself.

I sat next to the Prime Minister, by his left side. Governor Cuomo sat across from him and Matilda Cuomo and Leah Rabin sat next to one another, to the right of the Prime Minister. The conversation was warm and cordial. Cuomo, a leading American progressive, was well-liked and highly respected by Israeli Labour Party leaders.

In office just a few months, Rabin talked of his plans for pursuing peace in Israel and throughout the Middle East. He looked at each of us squarely, as he spoke in his deep, monotone, mournful voice. My eyes explored Rabin’s expressive face. It was a face chiseled with sadness, with eyes that had seen too much death and suffering. Later, I would learn that this man, haunted by the thought that he was leading young Israeli soldiers to their slaughter, suffered a nervous breakdown during the 1967 War—the war which secured the Golan Heights and the West Bank for Israel, and represented Rabin’s greatest military victory.

I can still hear Rabin’s voice, that somber voice, warning us of the grave threats to peace posed by political extremists among both his own people and the Palestinians. Just the day before in a public park in Jerusalem, I witnessed some of the Jewish extremists Rabin referenced. They tried to shout down Jerusalem Mayor Teddy Kollek—an effervescent, ebullient five-term Mayor—who was speaking at a public event. The Right Wing zealots—followers of ultra-nationalist and convicted terrorist Rabbi Meir Kahane– despised Kollek, because he believed that all faiths should be able to worship freely at their holy sites in Jerusalem. As a convert to Judaism, I admired Teddy Kollek’s respect for all religions.

I can still feel Yitzak Rabin’s penetrating gaze into my eyes, the firm yet gentle look of a man who had known love and loss, weakness and strength, sorrow and joy, victory and defeat. I can still see the sadness slip from his eyes, each time he spoke of his hopes for bringing peace to the land of his birth;

I can still feel the sweet contradiction in the strength of his handshake and the softness of his voice when he wished each of us “Shalom.”

It was the last word Yitzhak Rabin spoke to us.

Three years later, in November, 1995, Rabin attended at a peace rally in Tel Aviv, to support the Oslo Accords with the PLO which he & Peres had negotiated with Yasir Arafat, and for which he, Peres & Arafat would all be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

At the peace demonstration, Rabin sang the words to the “Song of Peace.” He folded the paper on which the words to the song were written, and gently placed it in his jacket pocket. Minutes after that, an assassin’s bullet ended Rabin’s life. The folded paper containing the following lyrics to the “Song of Peace “ (Shir L’Shalom) was found covered with blood:

“ Let the sun rise, the morning shine,

The most righteous prayer will not bring us back.

Who is the one whose light has been extinguished,

And buried in the earth;

Bitter tears will not wake him; will not bring him back.

No song of praise or victory will avail us.

Therefore, sing only a prayer of peace.

Don’t whisper a prayer—

Sing aloud a Song of Peace.”