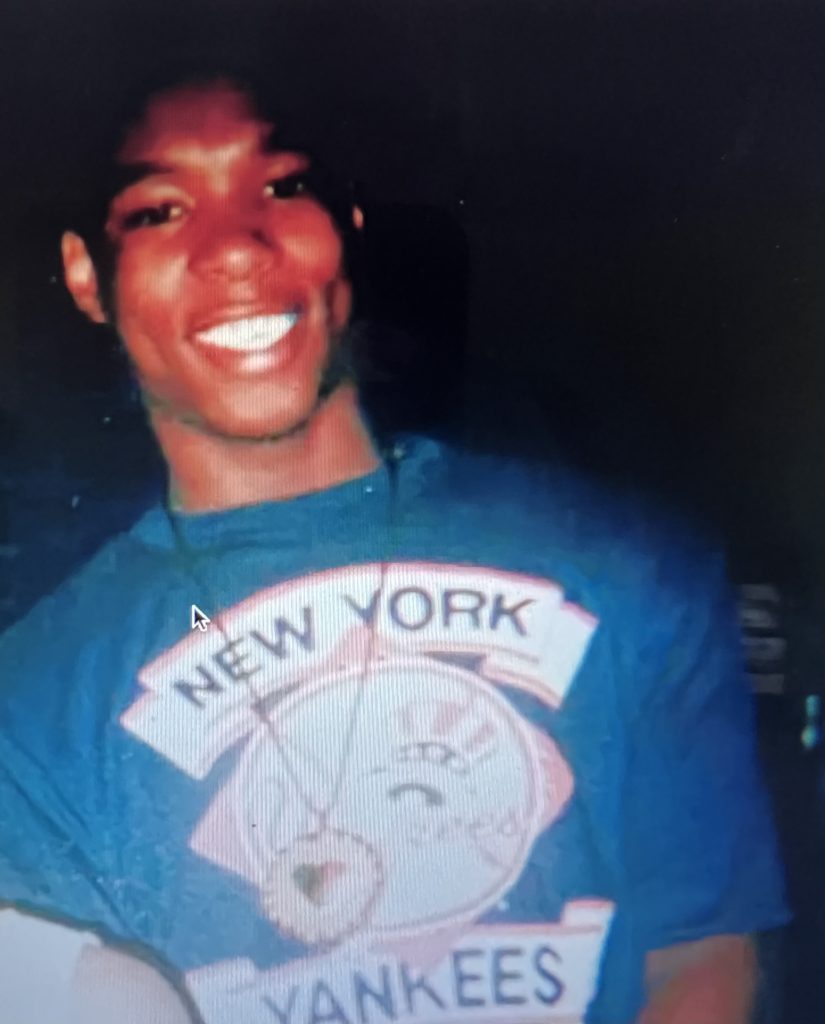

(Yusef Hawkins, 1973-1989)

Just a few days after the Confederate State of Florida announced it will start teaching the “benefits” of Slavery upon the enslaved, the Biden/Harris Administration proclaimed it will designate a series of national monuments to honor Emmett Till, the 14-year old Black child tortured, brutalized and lynched by Florida’s fellow White Supremacists of Mississippi, back in 1955.

The announcement came on what would have been Emmett Till’s 82nd birthday, clearly intended as a graphic illustration of the murderous racism and hate that is intertwined into nearly every sinew of American history. It was the equivalent of Joe Biden and Kamala Harris using the pulpit of the Presidency, to reopen Emmett Till’s casket, just like Mamie Till did 68 years ago, to force the world to see the real evil and inhumanity wrought by racial hatred upon her only child.

Stare at the body of that mutilated child, Florida; affix your eyes on the mangled manifestation of your immorality. We won’t let you erase it, nor the brutalization of millions of Black people enslaved, or ensnared in your still-cruel laws and customs, or thrown into camps of mass incarceration–the new, institutionalized face of Jim Crow.

I heard the news about Emmett Till’s national monuments today and first thought that he could have been my child, or my grandchild, since he was murdered at the same tender age that my oldest granddaughter has just reached. How easy, I thought, for my beloved granddaughter–an out, proud Lesbian–to be targeted by hateful people who view her mere existence as a threat.

I heard the news about Emmett Till today, and thought about a 16-year old Black child, Yusef Hawkins, murdered for wandering into an unfamiliar White neighborhood in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn, at precisely the “wrong” time, 34 years ago next month, during a long, hot New York City summer.

I worked with New York State’s Governor Mario M. Cuomo at the time, at 2 World Trade Center, when the news assaulted us that a mob of some 30 white men wielding baseball bats chased Hawkins—a young black face in an enclave of mostly white Italian-Americans—and then someone in the crowd shot him to death. Hawkins was innocently responding to a newspaper ad to purchase a used car, and the subway he took to arrive at the location, deposited him in Bensonhurst for the first time—and the last– in his short, beautiful life.

I was sickened by the brutal murder, and outraged at the young Italian tough-guys—John Gotti wannabes—who rushed to tell the tabloid and TV reporters that the “nigger” (their word) had no place in their neighborhood. I kept Cuomo informed all day of the rapidly unfolding events following the murder of Yusef Hawkins, drafted his official response, and knew that we’d be attending the Black child’s funeral in East New York, not far from where I was born.

The Hawkins murder by violent Italian-American punks haunted me for days. I knew these people. I left them behind to fester in their own ignorance, while I pursued a far different life, for a working-class, Italian-American kid. I knew these people, and I used all my strength to escape their grasp. I tried to push them away and out of my memory and experiences, but what good did it all do when a 16-year old Black child was dead?

I detested these wise guys who swaggered around their neighborhoods, swimming in their own ignorant smugness; despised them for their violence and the crimes they committed, and for what they made people think of us, and for how little they made us think of ourselves.

I blamed myself for Yusef Hawkins’ death, because, somehow, in my desperation to get out, to get away, I lost sight of how I might have changed some other life like mine; shown another young Italian-American kid struggling with his identity and place in the world, that there were avenues of education and compassion to escape from all of our own personal Bensonhursts.

Yusef Hawkins was my own child—just two years older than my own son, who too, was without guile, and trusting of other humans, regardless of race or background or neighborhood. Yusef was a child of the City which took his life, and no matter how hard I scrubbed, I could not get his blood off my hands.

So, I cannot think about children like Emmet Till without thinking of Yusef Hawkins, and of thousands upon thousands of others like them, who wander into a world of hostility and hatred, and cannot, like many of us, comprehend the depths of the heart of darkness.