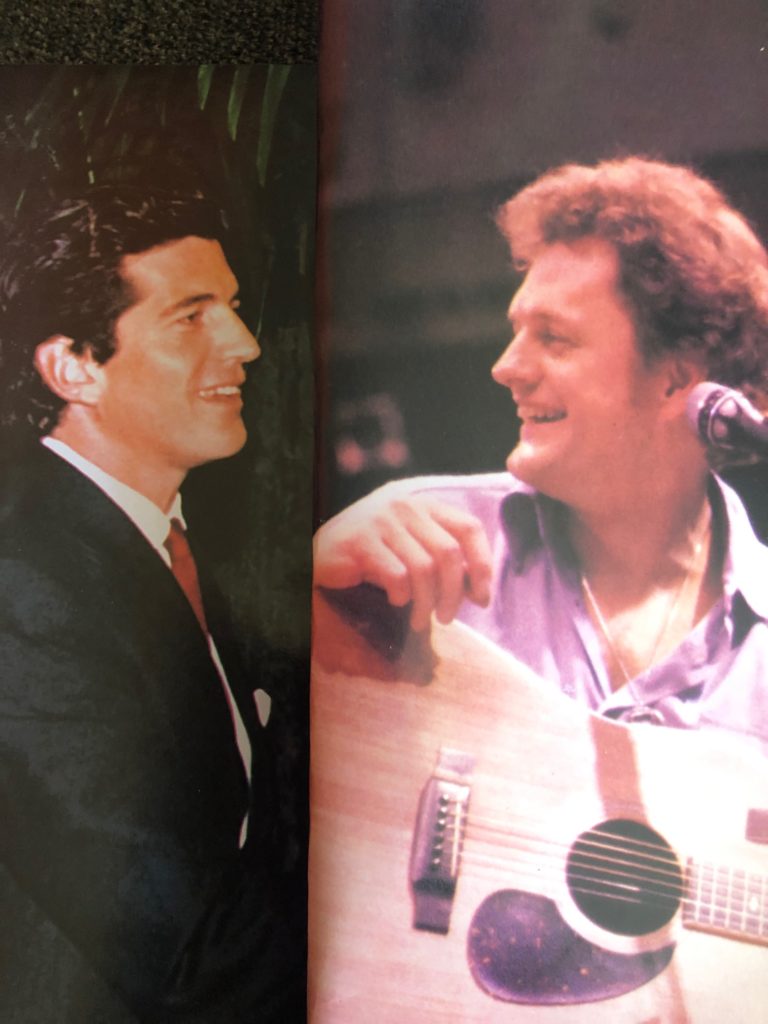

Harry Chapin & JFK, Jr: 38 years of Inspiration; Lives Worthy of Imitation.

By Steve Villano,

Chapter 4,

Copyright, 2021.

They were always there, right in front of me: Harry Chapin, and John F. Kennedy, Jr., linked in death on the same exact date — July 16.

They died 18 years apart, their age difference, when they were both killed in terrible accidents at 38 years old.

Chapin’s brief, shooting-star-of-a-life ended in the fiery crash of a small car on the Long Island Expressway; JFK, Jr.’s, in the crash of a small aircraft, somewhere off the coast of Martha’s Vineyard.

They were brothers in death, but their families — guided by strong women — and their mutual lust for life were intertwined in ways that one of Harry Chapin’s five children, Jason, would come to experience first-hand, in his work directly with JFK, Jr. and his “Reaching Up” non-profit organization.

The son of President John F. Kennedy founded “Reaching Up” in 1989—eight years after Harry Chapin died– to give greater access to higher education and training to healthcare givers working with individuals with disabilities.

The organization’s work not only enlarged the scope of the Special Olympics founded by JFK, Jr’s Aunt Eunice Shriver, but it also shared the compassion and common sense of the life-saving work done by a national non-profit co-founded by singer/songwriter Harry Chapin at the peak of his fame — WhyHunger — still tackling food insecurity in local communities 46 years after it was formed, as well as providing job skills to lift people out of poverty. Chapin and Kennedy were answering similar calls to serve others.

Jason Chapin, who worked with Governor Mario M. Cuomo and was elected to two, four-year terms on the New Castle Town Council in Westchester, County, NY, has, along with his four siblings, carried on his father’s work for WhyHunger and local food banks since 1975. He is the only Chapin to know JFK, Jr., and work with the “Reaching Up” organization and its City University of New York partner (CUNY) from 1995 to 2001.

“John was extremely passionate and dedicated to the organization, “ Jason Chapin said. “ I will always remember our Board Meetings which John chaired. He politely greeted everyone in the room when he arrived. He attended all of the annual Reaching Up Kennedy Fellows Convocations and was very friendly with the Fellows.”

It was precisely the same way JFK, Jr., greeted me at an early 1996 non-profit breakfast at New York’s Plaza Hotel which I attended as a guest of Jason Chapin’s. I was representing Downstate Medical Center in Brooklyn, and wearing a “We Believe in Brooklyn” button to boost Brooklyn’s visibility among the Manhattan political and media elite. JFK, Jr., who sat a few seats away from me at the circular table, spotted my button as soon as we got seated. He leaned over to me and whispered.

“My family believes in Brooklyn, too,” JFK, Jr. said. “We believe deeply in the Bed Stuy Redevelopment Project,” an important initiative started during the too short Senate term of his uncle, Robert F. Kennedy, when he was NY’s U.S. Senator, from 1965–68.

What JFK, Jr., may not have known then was how important Jason Chapin’s grandfather, John Cashmore, was to his own father’s election as President of the United States in 1960. Cashmore, Brooklyn Borough President from 1940–1961, delivered 66% of Kings County’s vote to JFK, helping him beat Nixon in New York State by five percent, and win NY’s 45 electoral votes, giving Kennedy the 303 Electoral votes he needed to win the Presidency.

I told JFK, Jr. how important the BedStuy project was to Central Brooklyn, the community served by our public hospital, and how important his own father’s example of public service was to me in guiding my life’s work.

“You probably get tired of hearing that from so many people of my generation,” I said to JFK, Jr.

“I never get tired of hearing it,” he said. “It makes me proud to see how many people my father inspired.”

Over the more than three decades I’ve known Jason Chapin, I’ve heard him say, with unending politeness and grace, the exact same words about his father, when people tell him Harry Chapin inspired them to commit their lives to fighting poverty, or improving public health, or helping refugees find access to food or shelter.

“I’m always amazed by how many people my father reached, how many lives he touched,” Jason says again and again.

Harry Chapin, like the Kennedys, was not content to sit still, and unafraid to use his celebrity to do good, performing 2000 concerts during his 10-year music career, with half of them as benefits, raising more than $6 million to fight hunger, and millions more on his radio “Hungerthons” with WhyHunger co-founder Bill Ayres, a former Catholic priest who Marched on Washington with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., in 1963—to pressure JFK, Jr’s father to pass Civil Rights and Voting Rights legislation.

As with JFK, Jr., Chapin was encouraged to take his activism, courage and compassion full-time to Washington, and run for the U.S. Senate from New York.

Harry recognized, as JFK, Jr., did with the creation of “Reaching Up” in 1989, that his name attached to any project could attract politicians, the media, the public and funding to the cause.

His crusade against hunger and poverty, and his successful campaign to create a Presidential Hunger Commission with the help of Senator Patrick Leahy (D-VT.) and President Jimmy Carter, exhibited the same instincts that propelled JFK, Jr., to launch “Reaching Up” and George Magazine: they both knew that politics and pop culture had merged, and that those in a position to use their fame to improve human existence, and to demonstrate their love for life, had a responsibility to do so.

Now, 40 years after Harry Chapin’s death and 22 years after JFK, Jr’s—both on July 16—their lessons of lending their celebrity, and giving their lives, to improving the lives of others, are more crucial than ever before. We need more public-spirited, fearless human beings like Harry Chapin and JFK, Jr., and to turn their inspiration into action.

###