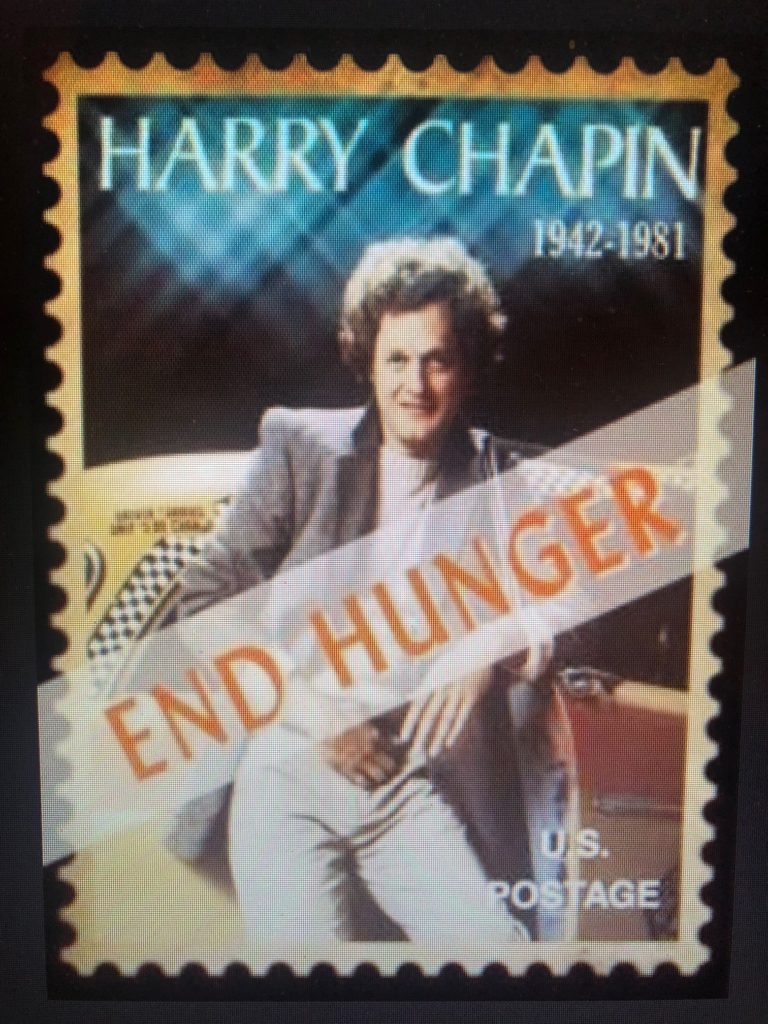

Harry Chapin: Hope, and Life, After Death

By Steve Villano, Chpt. 3

Copyright 2021

(It’s fitting that the largest tax credit in US History—a monthly payment for children (childtaxcredit.gov), which will lift one-half of America’s children out of poverty—is being implemented this week, which also marks the 40th Anniversary of Harry Chapin’s death. Chapin– inspired by his older brother James; the great anti-poverty champion and author of The Other America Michael Harrington; Harry’s spouse & partner Sandy Chapin; and his friend and former Catholic priest Bill Ayres, who followed the progressive Catholic Worker teachings of Harry’s great aunt, Dorothy Day—devoted the last decade of his life to fighting hunger and reducing poverty. The organizations which Harry Chapin founded, from WHYHunger to Harry Chapin Food Banks across the nation, continue to serve those most in need, four decades after Chapin’s death. The work of those anti-poverty organizations, and the extraordinary dedication of the Chapin family has carried forward Harry’s hope, and given his social justice work a life that is now longer than the time on earth enjoyed by the singer/songwriter.)

When Tom Chapin, the younger brother closest in age to Harry, got a call on that July day in 1981, from the Nassau County, NY, cop who recovered Harry’s charred body near the Jericho exit of the busy Long Island Expressway (Interstate 495), he knew something wasn’t right.

“What’s your relation to the deceased?” the police office asked.

Tom was taken aback. “ Deceased?”

Someone had died in a terrible car accident on the L.I.E. and his wallet was incinerated, destroying all of the victim’s ID.

“We have a body here, and the only way we can identify it is by this pocket watch we found on him with a name inscribed on it,” the Nassau County Cop said.

“What does it say, “ Tom asked, fearful that he already knew.

“It says: “From the Flint Voice. To a great American, Harry Chapin,” the cop said.

Tom Chapin felt as if he had been punched in the stomach, and that the world stopped. He knew that Harry always carried a cherished pocket watch given to him by Michael Moore, the documentary filmmaker, before Moore made any films or was known beyond Flint, Michigan.

As a pushy 22-year old, Moore had thrust himself into Harry’s face backstage at intermission of a 1976 Grand Rapids, Michigan concert, begging Chapin to do a benefit for his fledgling, muckraking publication, the Flint Voice.

“He said, ‘sure,’ I’ll do it,” Moore told a crowd at the Huntington, N.Y., Book Review bookstore in October, 2011, some 30 years after Chapin’s death, “and two months later he came to Flint to do a benefit concert for us. Harry came for five years, every year — even when Flint was down and out — sometimes doing two to five concerts a year. When Harry died it sent shock waves through the people of Flint because we kind of adopted him.”

What Moore didn’t learn, until years later, was that it was the inscribed pocket watch he gave to Harry Chapin out of gratitude for his generosity, that enabled his brother Tom to identify the body.

Chapin’s simple act of human connection, of wanting to improve life for the people of Flint, Michigan; his great act of love for a cause championed by another idealistic organizer, and his spirit of making the world a bit better, had survived the fire, even though his body had not. It was a metaphor for how Harry’s social justice work lived on, longer than his 38 years on earth.

“Yes,” Tom said to the cop after he finished reading the inscription on the pocket watch. “I’m Harry Chapin’s brother.”

“Then you may want to come down to the Nassau County Medical Center and identify the body,” the cop said.

The shock of Harry’s death spread slowly, stubbornly, with each call Tom Chapin made, as if, not even the truth could believe itself.

Family and friends flocked to the Chapin home in Huntington Bay, to be with Sandy Chapin and her children — the youngest of whom, Jason, Jen and Josh, were 17, 10 and 8 ½ years old.

Fans flooded the band shell at Eisenhower Park in East Meadow for a benefit concert to fight hunger that Harry Chapin was scheduled to give that same night, refusing to leave for hours, refusing to believe that the news they heard was real.

The day after Harry’s death, thousands of people spontaneously showed up in downtown Flint, Michigan, to pay their respects to someone who’s “greatest gift and the curse he lived with was that he always cared,” about them, and people like them—a lyric Harry prophetically wrote about folk singer Phil Ochs, who killed himself in 1976.

The profound and prolonged reaction to Harry Chapin’s sudden death, and the work of WHYHunger and Harry Chapin Food Banks around the country over the next four decades to pull people out of poverty and make millions of families less food insecure, was, and continues to be, a reminder of why Harry’s life mattered, well beyond his music.

Yet, performing artists like Billy Joel, considered a consummate musician and songwriter who has received every conceivable musical honor, along with selection into the Rock & Roll and the Songwriters’ Halls of Fame, had the highest praise for Harry’s artistry, as well as his activism.

“He wrote the best story songs,” said the singer/songwriter from Hicksville, Long Island, who wrote some pretty good songs himself. “ A lot of people said to me, ‘you wrote Piano Man?’I thought it was a Harry Chapin song.”

A slight grin brightened Billy Joel’s face, in the sunny front section of his motorcycle shop in the Village of Oyster Bay, Long Island.

“No I wrote that, I would say. Harry’s songs were about human beings, humanity. Whether his career was big enough, that’s not important. It was his impact.And he had an impact upon other songwriters that was all positive, all to the good,” said Billy Joel.

For Harry Chapin, as it was for one of his heroes, Pete Seeger, commitment to a cause, to his family and his craft, made his life full. Bruce Springsteen, who raised $2 million last December to fight food insecurity at the height of the COVID-19 Pandemic, has picked up the musician’s mantle of social justice leadership carried by Chapin, Seeger, Joan Baez, Phil Ochs, Chilean folksinger Victor Jara and many others over the decades.

In his comments at the December 7, 1987, Carnegie Hall Tribute where Harry Chapin was posthumously awarded a Special Congressional Gold Medal for his Humanitarian work — only the fourth musician in US history to ever be so honored, along with Irving Berlin and George & Ira Gershwin — Springsteen talked about the legacy of an activist artist like Chapin.

“ Harry instinctively knew it would also take more than love to survive,” he said, before singing a haunting rendition of Chapin’s song Remember When, “it was going to take hard work, with a good, clear-eye on the dirty ways of the world.”

In his own autobiography Born to Run: Bruce Springsteen(Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, NY, 2016, by Bruce Springsteen) Springsteen writes about his own “clear-eyed look at the dirty ways of the world,” after beginning his work with food banks and anti-poverty groups around the country in the mid-1980’s, following Harry’s death:

“I never had the frontline courage of many of my more committed musical brethren. If anything, over the years, too much has been made of whatever service we’ve provided. But I did look to develop a consistent approach. Something I could follow year in and year out, and find a way to assist the folks who’d been hit hardest by systematic neglect and injustice. These were the families who’d built America and yet whose dreams and children were, generation after generation, considered expendable. Our travels and position would allow us to support, at the grassroots level, activists who dealt, day to day, with the citizens who’d been shuffled to the margins of American life.” (P. 328).

At the Carnegie Hall Chapin Tribute concert in 1987, Springsteen acknowledged that Harry was one of those with such relentless “front-line courage.”

In fact, Harry was living the line he wrote in his own story song “The Parade’s Still Passing By” about Phil Ochs, the Civil Rights activist and anti-war folk singer who rivaled Bob Dylan for a time in the 1960’s, and killed himself in 1976, at the age of 35: “your greatest gift and the curse you lived with was that you could always care.”

Ochs had traveled to Hazard, Kentucky, to perform for the families of striking coal miners in 1963; to Mississippi in 1964 as part of the Caravan of Music to support the Freedom Fighters throughout the South; to Chicago, in the summer of 1968, to participate in demonstrations against the War in Vietnam at the Democratic National Convention; and to Chile, in 1971, following the election of Democratic Socialist President Salvador Allende to perform with the great Chilean political activist and folksinger, Victor Jara, who was executed four days after Allende was assassinated by Right Wing fascists, in 1973.

Och’s motivating mantra (There But For Fortune: The Life of Phil Ochs,by Michael Schumacher, University of Minnesota Press edition, Minneapolis, MN, 2018) could have been written by Harry Chapin, especially since both devoted significant portions of their careers, and earnings, to fighting poverty:

“ I have come to believe that this is, in essence, the role of the folksinger…I feel that the singer almost has a responsibility with political and social involvement. You can’t look at folk music as simply an element of show business, because it’s much deeper and more important than that.”(p. 74)

Harry’s cauldron of creativity and his own curse — similar to, but far more lasting that Phil Ochs’ — was the degree to which he cared about others, how much he desperately drove himself, how deeply he believed in things, and how determined he was to make his time on earth matter, and prove before he died—and for decades after—how much one person’s life could be worth.

###