We are a large, but silent, fraternity, we sons who have lost our fathers. We look at each other when the topic of one of our fathers’ deaths comes up, lock eyes for a moment and then quickly look away, for fear of awakening our own pain, never really asleep; lurking just below the surface and easily aroused by a place, a face, anything, anything that reminds us of our fathers.

When we learn, for the first time, that each of us are sons without fathers, we sometimes embrace, but are uncertain how to comfort each other to ease the pain of loneliness left by a dead man we once loved. Rarely, do we open up to each other to talk about the hole in our souls left by our missing fathers. We change the subject, averting our open wounds, just as we did our eyes.

We are not as smart as women, we stupid, vain, posturing men. We think we can bluff our way through the bottomless ache we feel, and believe we are meant to bear it alone because that, after all, is what men do—what we were taught to do by the fathers we mourn.

Each time I hear of a friend’s loss of his father to cancer, or a heart attack, or simply to time, I watch his eyes gather tears which never fall because he doesn’t know how to let them go. I stammer and search for something to say, something to save my friend from spinning down into that dark cavern of grief where I spent far too many hours. I grab his shoulder and struggle to let him know that I have been where he now dwells, and lived through it, though not without difficulty.

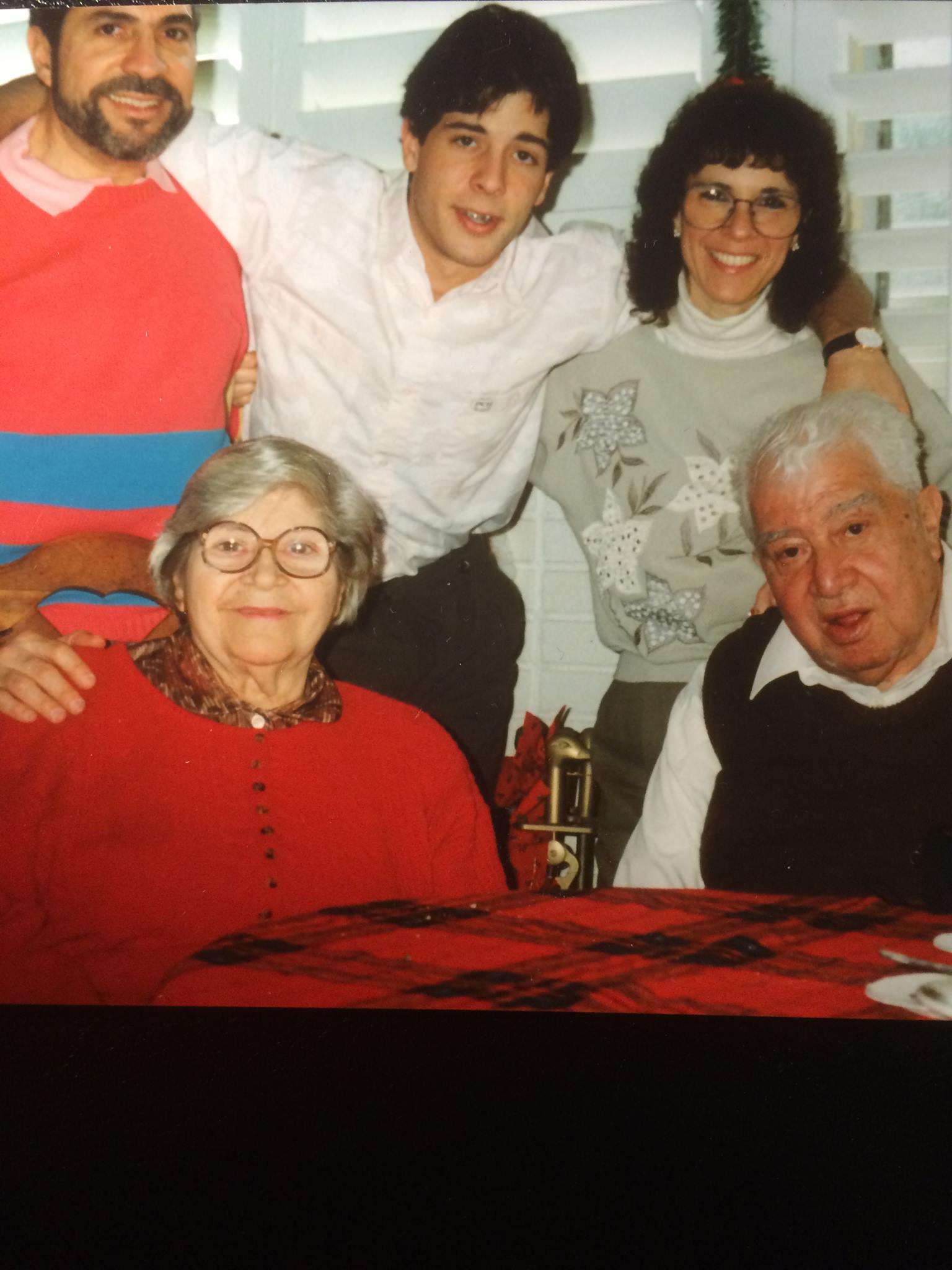

This is another Father’s Day without my father. He died on my 21st wedding anniversary, making each anniversary that follows a bittersweet occasion. Each day for weeks, I watched my father die a painful death from cancer, until the disease paralyzed his back and legs—a merciful numbness sparing him from feeling the torture of each one of his body’s systems shutting down. Each day, as he edged closer to the end of his life, I sat by his bedside, reading him the sports section and reciting to him last night’s Yankee boxscore.

I acted as I had been trained to behave as a man, staying strong for my mother, my sister and my father’s surviving sisters, most of whom are gone now, too. When no one else was around, I took long walks along the beach and cried uncontrollably, praying for the strength to make the right decision when my father pointed to the clock above his bed, mouthing the words “time to go.”

My father spared me that terrible task, choosing to make his final decision himself, demonstrating far more dignity in death, than he had in life. In the end, he gave me a gift that many other sons without fathers were not as fortunate to receive: he let me watch him take his last breath, and utter the last words he heard, which were “I love you.”

I still think of my father often these days, and catch myself wanting to call him to talk about the Yankees or the Belmont Stakes or the Warriors, or just to hear his voice, or hear him say my name. Each Fathers’ Day reminds me how much I love being a father with a son, and how painful it still is, years later, to be a son without a father.