Elie Wiesel’s lessons, his relentless bearing of witness, and the fire to fight for humanity burning in his soul, never leaves me.

Jan 28, 2026

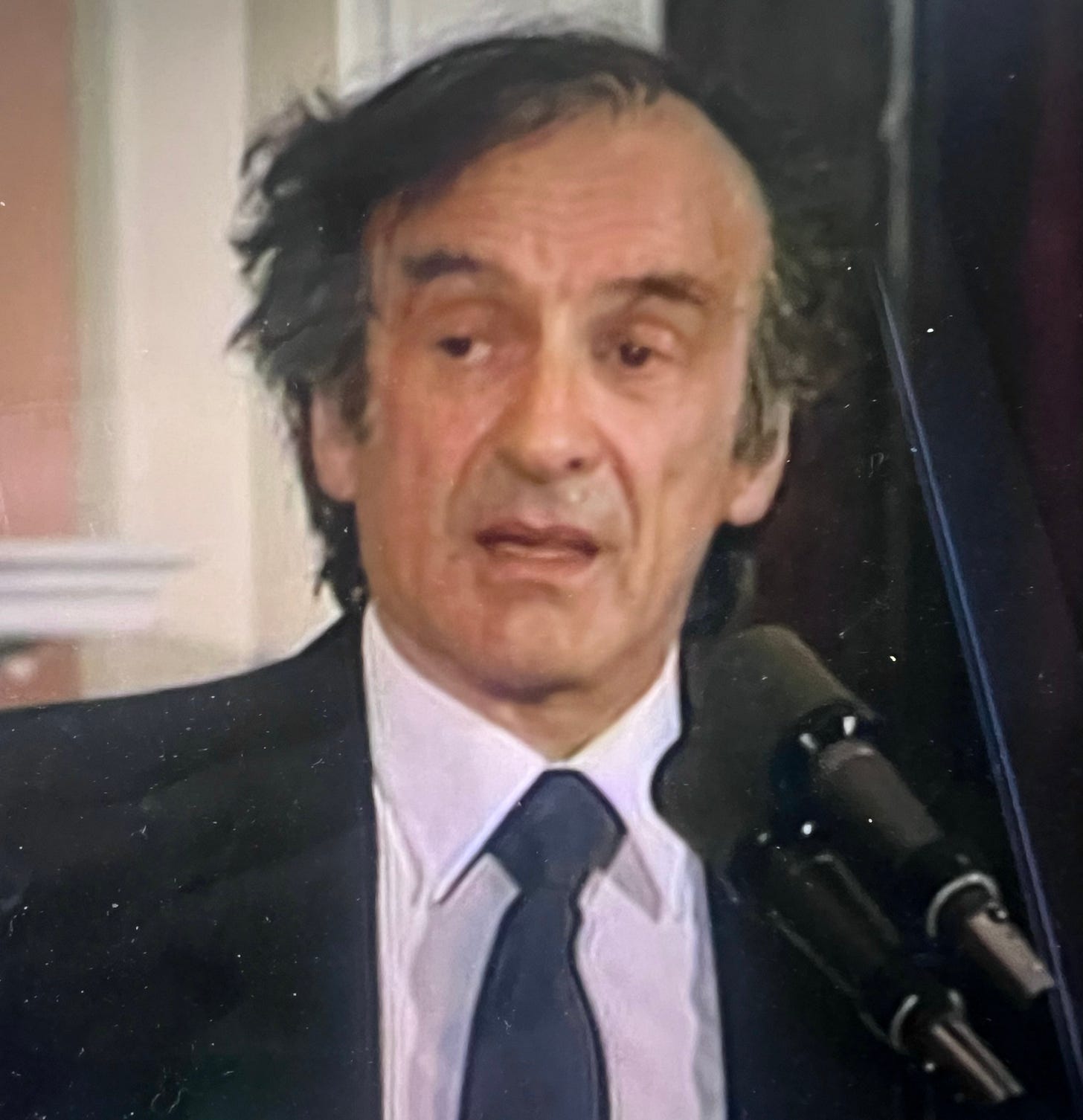

(Nobel Peace Prize Winner Elie Wiesel speaking at the White House, April 19, 1985, challenging President Reagan’s decision to visit the German Military Cemetery at Bitburg, where Nazi SS Officers were buried)

I watched PBS’ Elie Wiesel: Soul on Fire this week, the biopic of the Holocaust survivor and author of 47 books whose whose rich, wrenching collection of writings, essays and interviews have borne witness to the Nazis extermination of 6 million Jews, and millions of non-Jews.

The documentary aired as part of the Public Broadcasting Series of “American Masters” during Holocaust Remembrance Week. Ironic, I thought, since the anti-Semites who wrote Pogrom 2025—declaring the US to be a “Christian Nation” (non-Jewish) and their apologists on the Extreme Right and within the Trump Administration—who accuse everyone else of anti-Semitism—worked mightily to erase PBS from American consciousness and culture.

Wiesel’s life, and his life’s work, have been an instruction and moral guide for many of us. His writings, particularly in his seminal work Night which described his life as a Jewish teenage boy first deported to Auschwitz with his family, and then sentenced to Buchenwald, where he watched his father die in front of him, were a powerful part of my personal education on my path to converting to Judaism 46 years ago.

While I didn’t agree with Wiesel on everything, particularly on the rights and legitimacy of Palestinians, and the future of Jerusalem, I shared his deep outrage over President Ronald Reagan’s decision in May, 1985, to visit Bitburg Cemetery in Germany, where Nazi SS Officers were buried.

I was 5 years into my life as a Jew than, and only five months into my work with then-Governor of New York State, Mario M. Cuomo.

Immediately after Reagan’s decision to visit Bitburg, and Elie Wiesel’s nationally televised appeal in the White House for Reagan not to go, I accompanied Mario Cuomo to a public presentation at John Glenn High School on Long Island, just a mile from my home in East Northport, where he spoke to 1,500 high school students about “Human and Civic Values.”

Cuomo was his usual eloquent self explaining to the mostly-white, middle class students about how his immigrant parents, who spoke no English, had such a profound influence upon his life.

“They just showed us by living every day in that grocery store, by working, they taught us what strength was; they taught us what commitment was, “ Mario Cuomo said to the students. “They came from other parts of the world and had nothing…It can only happen here.”

The students, filling every bleacher seat in the gymnasium and covering much of the hardwood floor, applauded wildly. Then, Cuomo asked for questions from the audience.

A young, sandy-haired female student rose to her feet, cleared her voice in front of the standing microphone, and looked straight at Mario Cuomo, whose gravitas and deeply-lined face could often be intimidating.

“Governor,” she asked, “If you were President, would you have gone to Bitburg?”

Cuomo, rarely at a loss for words, bought some time by explaining about President Reagan’s recent visit to Germany’s Bitburg military cemetery. He described the intense feelings on “both sides,” and then, in a long apologia for Reagan, expressed understanding for the President’s difficult decision.

“I probably would not have gone to Bitburg,” Cuomo said, “but I can respect the President’s decision to do so.”

In heavily Republican Suffolk County, which Reagan won overwhelmingly in 1984, not a murmur was heard from the crowd. I cringed.

As a relatively new convert to Judaism, I was furious with Cuomo for sounding like he was pandering to Long Island Republicans on a matter of moral clarity, as articulated brilliantly by Elie Wiesel to President Reagan on April 19, 1985, just a few weeks before:

“That place, Mr. President, is not your place,” Wiesel said turning directly to Reagan at a White House ceremony. “ Your place is with the victims of the SS.”

I fumed all afternoon on the way back to our World Trade Center office about Cuomo’s cavalier comments, knowing that if I swallowed my anger over his answer I would dislike myself, and him. I was determined not to be silent on something which struck me to the core.

I took the Long Island Railroad back home that evening and dashed off a three-page memo—there was no internet or email in 1985—written like a legal brief, which was Cuomo’s preferred way of reading information:

“In your effort to be fair to President Reagan, you may have unintentionally been unfair to Jews and Gentiles whose deep feelings about the Holocaust I know you share,” I wrote.

A few weeks earlier, I had accompanied Mario Cuomo to Madison Square Garden, where he addressed thousands of Jews and their families at the Warsaw Ghetto Commemorations Service. Cuomo’s voice resonated throughout the high rafters of the Garden:

“For to confront the fact of the Holocaust is to look into the heart of darkness to comprehend the scope of evil in this world, to measure the human capacity to hate and to murder and to destroy. It is to acknowledge the abyss.”

His words were still ringing in my ears when I heard Cuomo’s lame response to the Bitburg question. I could not believe he was sanctioning Reagan’s insensitive trip on the heels of his bringing Warsaw Ghetto survivors and their families to tears with the depth of his understanding and compassion about human suffering and the Holocaust.

I argued to him, in my Wiesel-inspired brief, that as a “new Jew,” I was deeply offended. I knew I had his attention and was in a position few others were privileged to occupy to make my outrage known:

“I am keenly aware of the sentiment of some segments of the Jewish community of reluctance to criticize the President’s Bitburg mistake, for fear of an anti-Semitic backlash. As a Jew, and head of the Social Action Committee at my Temple, I understand that sentiment, but I do not agree with it.”

I went on to write that Reagan’s actions: “are not deserving of your understanding nor your defense. Your public thoughts, public words and public deeds mean too much to Jews and Gentiles alike to be miscontrued as supportive of the President.”

I had already faced down my mother’s fierce Catholicism and latent anti-Semitism on my decision to convert to Judaism. By comparison, discussing Bitburg with Mario Cuomo was easy, and very, very clear.

Shortly after the Governor received my memo, he called me, and we discussed Bitburg and Reagan at length, as well as my decision to convert to Judaism, after a lifetime of being raised a Catholic. The memo transformed my relationship with Mario Cuomo; he thanked me for sending it, and told me to feel free to communicate with him my thoughts on how we could better approach any issue.

Six years, and many such memos later, Mario Cuomo asked me to serve on a task force with Elie Wiesel, established by then-NYC Mayor David Dinkins, called “Increase the Peace.” It was a task force to rebuild Black-Jewish relations in NYC, following a series of racial incidents in Crown Heights Brooklyn, where I was born.

Our first meeting was held in Elie Wiesel’s Manhattan East Side apartment, with Dinkins Administration officials, some corporate executives, and Elie and Marion Wiesel, Elie’s wife and partner of many years.

I entered the Wiesel apartment as if it were a Cathedral or a sacred Synagogue. Books and bookshelves covered every square inch of every wall that wasn’t a window. They were not decorative books, but books which had visibly been read and re-read over and over again. I thought of the pages of Night, where Wiesel recounted his father calling out his name, “Eliezer,” only to be answered by a Nazi SS Guard giving his father “a violent blow to the head.”

I thought of a young, terrified Elie Wiesel going to sleep that night, January 28, 1945, in the bunk above his father’s bunk at Buchenwald, when his father was still alive, and waking up: “at dawn of January 29. On my father’s cot there lay another sick person. They must have taken him away before daybreak and taken him to the crematorium. Perhaps he was still breathing…His last word had been my name.”

I was enveloped by every book reaching out to me in the Wiesel’s living room, and thought again of Bitburg, and how this wise and fearless witness was compelled to “speak truth to power,” and how he still inspires me, and countless others, to keep that fire kindling in our souls.