Cruel and random acts of violent madness, on the 30th Anniversary of Tobias Wolff’s masterpiece, in a country run by violent madmen, sowing violence & madness.

(This month, marks the 30th Anniversary of the publication of the writer Tobias Wolff’s extraordinary work of fiction “Bullet in the Brain,” in the New Yorker Magazine. The first time I came across the story was when it was read aloud to me and a few other classmates by my friend and fellow classmate Jefferson Spady in a screenwriting workshop in the Greenwich Village living room of our professor Loren Paul Caplin, just a few years after the piece was published. Wolff’s story transported me into the very setting where it occurred, and then stopped me cold by the sheer power of following the trajectory of the bullet which had been fired, at point blank, into the protagonist’s brain, stopping time and concentrating memory.

For decades, I have not been able to get this story out of my mind, and imagine what final thoughts might remain in my own brain during my fleeting nanoseconds of brain life. Lately, when violence and life have become more random and chaotic, Wolff’s “Bullet in the Brain,” has grabbed me by the throat. Perhaps it’s because of the daily drumbeat of intentional violence against human beings in Gaza, in the homes of innocent immigrants looking for a peaceful life, and in the quiet catastrophes of children and adults dying for lack of food, or medical care, or available vaccinations, “Bullet in the Brain” is ever-present to me now.

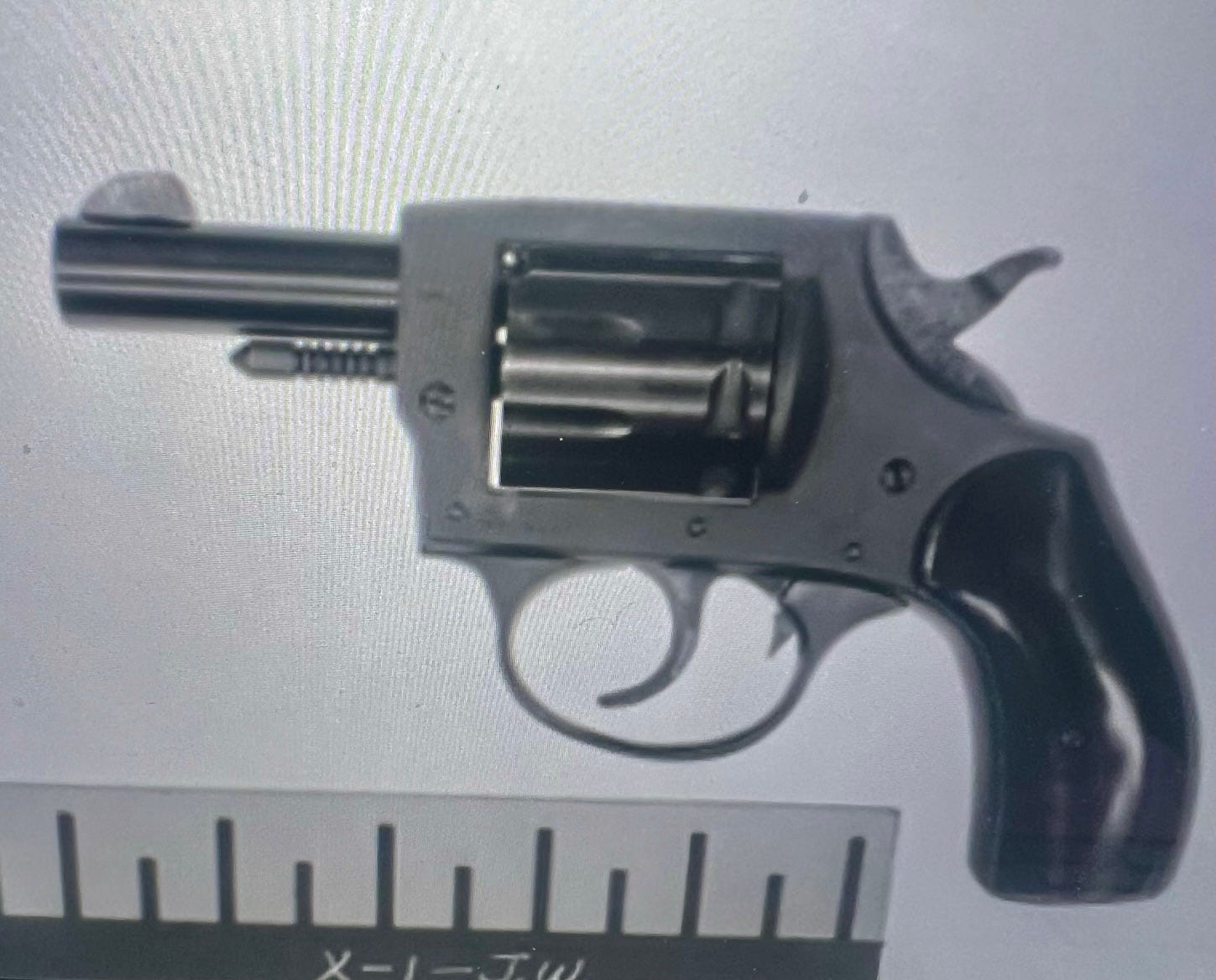

In recent days, it will not let go. Each time I learn of another insane, anti-human action by Trump or the severely emotionally damaged Stephen Miller, or Trump’s HHS high (ex-heroine junkie) executioner Robert F. Kennedy, Jr, I think of each action as another bullet into the brain of Robert F. Kennedy, the father, who was assassinated by the gun pictured above. Only this time, the bullets are being fired by RFK’s own son, into his own father’s head and into each of ours, are aimed at killing any last second thoughts Robert F. Kennedy, the father, or we, might have had about the faces of the peoples’ lives he touched and helped; the same suffering humans Trump & RFK, Jr.s twisted public policies are intentionally murdering. This piece of mine is a tribute to the work of Tobias Wolfe who beseeched us to think about such things, and an attempt to write these daily bullets of cruelty out of my own brain.

In some places you’ll recognize some of the brilliant words and phrases of Wolff’s; if I did a half-way credible job, I hope you’ll recognize a similarity in style, and the same sound of a human being’s primal scream against madness.)

The line felt like it was endless, even though he had patiently waited his way up toward the front. Angelo Nessuna couldn’t get to his local Florida pharmacy until just before it closed and now he was stuck behind two big-haired, wrinkly-skinned White women whose loud, stupid conversation about Trump not possibly being a pedophile because he had so many children, put him in a foul mood. His wife, Rose was with him, sitting quietly in her wheelchair, hands folded in her lap.

A retired NYC cop, Angelo was rarely in the best of moods anyway following a career spent arresting petty criminals for stealing milk, or shoplifting cheap jewelry, and breaking up domestic disputes between frustrated men and the women they pulled down into their despair. He felt lucky having gotten out of the South Bronx neighborhood before street drugs laced with heroine moved in, littering the Grand Concourse with almost as many dead bodies in doorways as there were Yankee fans.

He moved to Florida when it was still affordable to get away from those fucking New York City winters. He hated walking his beat in the dead of winter, and he hated ice more than the perps he arrested. Every one else on the Force talked about “living the dream” in South Florida, and he wanted to have a taste of it while there was still some left.

So Angelo and his wife Rose bought a small single story house in Margate, in a community of other small, single story homes surrounded by crabgrass and palm trees. Rose spent her days kibbitzing and playing cards with her friends at the community’s pool and Angelo was content to keep in shape by working out everyday in the tiny gym inside the community’s clubhouse.

After a while, and he’s not too sure exactly how long it was, Rose’s sitting out in the hot Florida sun for hours gave her skin cancer. For years she had the mean-looking moles on her body biopsied and then removed, and would joke about them to friends by saying “we Italians are mole-ly people.” Still, she wanted to play cards in the sun with her friends because, well, because that’s what they did in Florida, living the dream.

On one visit to her Dermatologist, who had a six-month waiting list for appointments, Rose, with Angelo by her side, was told that her skin cancer had metastasized and spread into her bones. She began to lose weight, and hair, and Angelo, still strong and fit by working out every day, would pick her up and help her across the street to the community pool, where she met her friends to play cards and smoke cigarettes. More and more, now, they would play in the shady parts of the pool area, out of the sun.

Rose was able to keep functioning and laughing her raspy, smokers laugh thanks to a fancy new wheelchair, and a parade of pills prescribed by her oncologist, which Angelo sorted out for her every Sunday, placing them lovingly in a light-blue, 7-compartment pill container, each compartment bearing the first initial of that day of the week.

When the COVID pandemic hit, and vaccines became available, Rose, over age 65, and with a serious health condition, was at the top of the list for vaccinations, and later for the over-the-counter COVID controlling drug, Paxlovid.

The pharmacists at the local CVS drug store in Margate all knew Angelo Nessuna. He was there a few days a week filling the prescriptions on all his wife’s medications. He had terrific insurance and drug coverage from his decades of work as a public servant for the NYPD, and they all loved to help out an ex-cop who devoted his life to helping others. A few of the women who worked at the store liked to flirt with Angelo, admiring his biceps and broad chest that came from his years of working out, clearly visible through the light shirts he wore most days in the Florida heat and humidity. They told him he looked like George Clooney, and he flashed a glorious, shy smile at them.

The pharmacy had just posted a new sign in the window and a group of customers were gathered around it, chatting, The sign literally shouted its’ message: “HHS SECRETARY ROBERT F. KENNEDY, JR, HAS ORDERED THE END OF THE PRODUCTION OF THE COVID VACCINE. We have very limited supplies left, and will distribute those on a high-need basis. Please be patient and courteous to your neighbors.”

Angelo spotted the sign the other day, but didn’t pay too much attention to it because he knew Rose was one of those high-risk patients, and that, besides, everybody at the Drug store knew him and liked him and knew about Rose’s condition. That night, worried about some crazy stories about vaccine shortages he saw on Fox News, he rushed into the local CVS right before they closed, pushing Rose in her wheelchair, who was having difficulty swallowing. He feared that she had already been hit with the new stubborn strain of COVID that attacked the throat first. All he could think about was getting her vaccinated, getting her medication and getting her home.

One man toward the middle of the line, a few rows behind him, started shouting.

“They’re gonna run out before we get to the counter,” the chubby, wild-haired, heavily tattooed man was repeating at the top of his voice to everyone around him.

The two loud women in front of Angelo at the beginning of the line suddenly got silent, and looked nervously at the overweight man, sweating and breathing heavily, as he got out of the long line and moved around people toward them, in the front.

Angelo, saw the expressions change on the faces of the two women, and turned to see the heavy, sweating man coming at them.

“I’m fucking tired of waiting,” he was shouting, his eyes crazed with rage.

Angelo had years of training as a NYC cop diffusing tense situations, and he knew that the best approach was to slow rising tempers down, and allow everyone to catch a breath. He turned around, and stepped out of the line, right in front of the approaching, and agitated, man.

“Calm down,” Angelo said in a strong, controlled voice. “We’ll all get our turn. I’m sure they wouldn’t have let all of us in the store if they didn’t have enough vaccines and medication to go around.”

The heavy-set, heavily tattooed man challenged Angelo.

“Oh, yeah. How the fuck do you know? Did you pay somebody off in here? “

Angelo, stood his ground, didn’t flinch one muscle of his tight body, and responded: “Look. We’re all in this together. We just have to be patient and civil to one another, and this will all work out.”

The wild-haired man shook his head violently.

“Easy for you to say, asshole. You’re pushing a woman in a wheelchair. You’re probably doing that just to get special treatment,” he said, motioning to the wheelchair.

Angelo’s eyes widened as he glared at the man. He took a deep breath, turned around, and gently pushed Rose’s wheelchair up right next to the counter, whispering to her, “wait here, I’ll be right back.” Everyone else in the line was silent. Angelo started to turn around.

The overweight, sweating, wild-eyed man had charged up behind Angelo quickly, pulling out a handgun from his cargo pants pocket and pointed it up against Angelo’s smooth silver-grey hair. Florida, was, afterall, a place where anyone could carry a weapon anywhere, and conceal it anyway at all.

Trying to defuse the dangerous turn of events, Angelo raised his two hands to signal surrender.

“Okay, okay, I get that you’re upset, “Angelo said. “Let’s just calm down so we can all be reasonable here. Capisce?

“Oh, I capisce,” the wild-haired, wild-eyed man said, and before Angelo could say another word, he fired one shot into Angelo’s left temple, splattering blood and brain matter all over everyone around him, including Rose, still sitting with her hands folded in her wheelchair, and the two big-haired wrinkly skinned White women who were sure Trump could not be a pedophile.

Precisely as Tobias Wolff described in his original story, Bullet in the Brian, published in the New Yorker, September 17, 1995, here’s what happened when the bullet entered the skull:

“The bullet smashed Anders (Angelo’s) skull and plowed through his brain and exited behind his right ear, scattering shards of bone into the cerebral cortex, the corpus callosum, back toward the basal ganglia, and down into the thalamus. But before all this occurred, the first appearance of the bullet in the cerebrum set off a crackling chain of ion transports and neurotransmissions. Because of their peculiar origin, these traced a peculiar pattern, flukishly calling to life a summer afternoon some forty years past, and long since lost to memory. After striking the cranium, the bullet was moving at nine hundred feet per second, a pathetically sluggish, glacial pace compared with the synaptic lightning that flashed around it. Once in the brain, that is, the bullet came under the mediation of brain time, which gave Anders (Angelo) plenty of leisure to contemplate the scene that, in a phrase he would have abhorred, “passed before his eyes.”

It is astonishing that Angelo did not remember, given what he did remember. He did not remember his first lover, Carol, or what he had most madly loved about her—her unembarrassed carnality, and unabashed joy of sex. He didn’t remember how his parents, who barely spoke English, ragged on about this “Jewish girl, with loose morals.”

Angelo did not remember his wife, Rose, whom he had also loved (as did his parents) before she exhausted him with her regimentation and predictability, and incessant smoking, which made him take long walks and stay out of the house just to get some fresh and his own precious space.

He did not remember Rudy Giuliani’s smug, self-satisfied face, as he and other Cops in his precinct walked past the then-Mayor just for show, nor did he remember the sea of faces—one face now— of the people whose petty arrests he made, nor the endless sameness of all the bodegas along the all same blocks he patrolled for years.

Angelo did not remember the complete text of every one of the Bill of Rights, which he had committed to memory in his youth so that he could make his parents proud, while also letting them know that his life would not be anything like theirs. He did not remember the night his mother stood, huge breasts heaving with each breath, in front of his father frothing with rage, waving a shotgun and threatening to kill the “son-of-a bitch” who made his sister pregnant.

He did not remember 9-11, nor how he was off-duty that beautiful, blue-sky day, and he spent days of his own time sifting through the piles of stone and ash and metal, alongside Cops and Firefighter and civilians, searching for a bone, or a finger, or a photograph of a child that sat on someone’s desk.

Nor did Angelo remember seeing a woman leap to her death from the sixth floor of a burning Bronx tenement building just days after his only son was born, or his shouting “Jesus Fucking Christ have some fucking mercy,” when her dark brown body, clad in a housedress just like his mother wore, crumbling hard into the ground, snapping her neck.

Angelo did not remember when his son deliberately crashed his car into a tree, or got his ribs kicked in by unidentified masked ICE agents, pretending to be policemen, at a rally for immigrants rights, or bailing his son out of jail, time after time after time, in cities and towns across the country.

This is what he Angelo remembered: (first paragraph entirely from Tobias Wolff; the rest paraphrased with poetic license)

“Heat. A baseball field. Yellow grass, the whirr of insects, himself leaning against a tree as the boys of the neighborhood gather for a pickup game. The captains, precociously large boys named Burns and Darsch, argue the relative genius of Mantle and Mays.”

He did remember when the last two boys arrived for the sandlot game, Frankie Testagrossa, his best friend, and Eddie Cruz, a wiry brown kid from across the street, who had moved to the Bronx from Puerto Rico. Angelo never met Eddie Cruz before, but had seen him watching this group of white boys, mostly Italian and Irish kids, play ball for hours on one of the few empty lots around.

Angelo did remember Eddie saying hi and flashing a big, bright grin, and remembers being immediately attracted to him, and picking him for his own team because he saw something special in this kid, despite Frankie complaining that he “don’t want to play with no Spics.”

“You play with him or you don’t play with me,” Angelo remembers telling Frankie, and nobody said another word until they finished choosing sides, and Angelo asked Eddie Cruz what position he wanted to play.

“Pitcher,” Eddie Cruz says. “Pitcher. El Corazon. The heart,” and he tapped his chest, and flashed his beautiful, guileless smile.

Angelo stared at Eddie Cruz, and noticed his large brown, bright almond eyes, and long graceful eyelashes. He wanted to hear him repeat what he’s just said, but he knew better than to ask. The others will think he’s being a jerk, or worse, was sweet on him. But that was’t it. Angelo is strangely aroused, elated, and made lighter, by those final two words “El Corazon;” their pure unexpectedness and their lilting music. Angelo took the field in a trance, repeating those words to himself.

The bullet is already in the brain; it won’t be outrun forever, or charmed to a halt. In the end, it will do its work and leave the shattered skull behind, dragging its comet’s tail of memory and hope and talent and love onto the cheap tile floor of a CVS drug story in Margate, Florida. That can’t be helped. But for now, Angelo can still make time. Time for the shadows to lengthen on the grass, time for to look up at the clear blue cloudless sky, time for Eddie Cruz in go into his wind-up, and to softly chant, El Corazon, El Corazon.”

(NB: No AI (artificial intelligence) was used in this updating and paraphrasing of Tobias Wolff’s work. The author does not know how to use it, nor care to. Only natural intelligence and humanity were used.)