More than 30 years ago, my own father was a victim of profit-centered health care, when a doctor told us “the corporation didn’t intend for this equipment to be used this way.” To keep him alive.

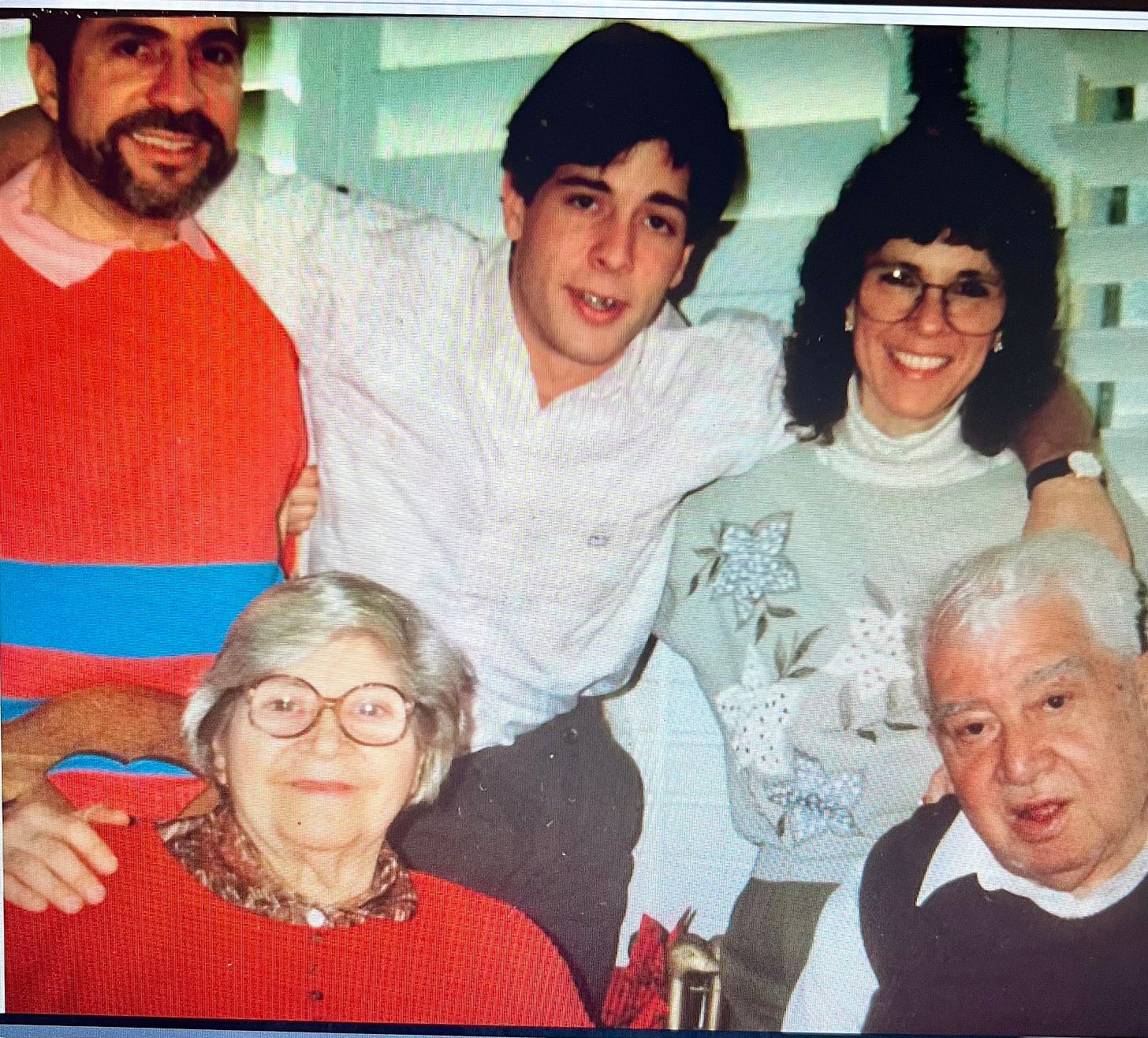

(Our last Christmas with my father, lower right, 1992. He died 5 months later, when his HMO repeatedly mismanaged his healthcare.)

The tragic killing of the CEO of United Health Care earlier this month ripped apart a health care corporation—and a broader, private health care system—that, for more than three decades, has put profits ahead of patient-centered care.

The cold-blooded, intentional murder of anyone—corporate executive or Palestine child— is a terrible, violent act, far outside any moral universe which rightfully condemns the denial of life, or life-saving healthcare, to any human being.

My father, a 78 years old, World War II Veteran, was a member of an HMO, once among the largest in Southern California. He has been dead for 31 years, and that specific company has been been out of business for decades, but its’ practices of prioritizing profits over patients, are more pernicious than ever before in the private healthcare industry.

My father’s case is illustrative of many others like it, with which families without wealth or influence can identify. It should be taught as a case study to healthcare executives, and medical school students, as a glaring example of the worst medical & business practices to avoid at all costs. It should serve as a guide to understanding why so many Americans are incensed at the spreadsheet-driven, corporatization of care for those we love. As the late US Senator from New York Daniel Patrick Moynihan famously wrote, “healthcare should not be a commodity.”

In the late winter, 1993, my father was experiencing difficulty urinating and began complaining of a pain in the middle of his back. A gruff, overweight Italian man, my father rarely went to “the doctor” or complained about his health. One of the rotating crop of HMO physicians who finally agreed to see him in person, said that at his age, “it wasn’t unusual to experience difficulty urinating, and that the back pain was probably the result of a draft you caught.”

He had been given the brush off by the HMO’s “gatekeeper”—a title designed to communicate the message that only certain patients made it past the gates of admission to the healthcare system. My father accepted the physician’s cursory diagnosis. After all, he was a “doctor,” my father said.

As the weeks went on, his urinary problems and back pain worsened. He began to wet himself during the night, and the pain in his back was making it difficult for him to rise up out of his reclining chair during the day. After much coaxing, we persuaded my father to see a urologist. Our family became insistent for the HMO to schedule an appointment with an urologist, and the corporation finally relented.

The HMO-assigned urologist diagnosed my father as having a bladder infection and recommended that he drink lots of cranberry juice to “clear it out of his system.” He was also prescribed an antibiotic and the pain in his back was again dismissed as nothing serious.

I described my father’s symptoms to an Oncologist friend of mine in New York who urged that we immediately get my father tested for Prostate cancer. We insisted that the HMO’s urologist see my father again, administer a PSA blood test, and do a DRE (digital rectal exam)—two simple and standard tests which, considering my father’s age and his symptoms, should have been done routinely during his first visit.

The results of the PSA test confirmed our fears: my father had an aggressive tumor that had already advanced beyond his prostate. The HMO’s urologist informed me by phone—some 2700 miles away—that my father’s cancer had not yet advanced into my father’s bones.

“What about the persistent pain in his back?” I asked.

The urologist continued to cling to his theory that my father may have caught a draft in his back.

Within one week’s time, the HMO’s urologist—who had spent a total of 30 minutes with my father during two office visits—told him that he had prostate cancer, and recommended surgical removal of my father’s prostate and testicles. For a street tough guy from Brooklyn, this was a lot to process.

I pointed out to the HMO’s urologist that my father had a low Gleason Count, and a high PSA—usually red flags for prostate cancer. I asked if he had an abnormal bone scan. The Urologist informed me he had not.

Increasingly, the evidence was building that my father’s healthcare was not being properly managed by his, so-called, “managed care” provider.

“Couldn’t hormone therapy be sued to decrease my father’s testosterone level, as long as his bone scan was not abnormal?’ I asked.

Yes, it could, the HMO’s urologist told me.

“Was it too much trouble to have explored such a possibility in the first place, “ I asked, “before immediately jumping to the conclusion that surgery was necessary? What about radiation therapy?”

The HMO’s urologist informed me that my father could be given a combination of injections, pill, and alpha blockers—which would have the side effect of lowering my father’s blood pressure.

I asked the HMO’s urologist if he was aware that my father was already taking medication to lower his blood pressure. The urologist told me he wasn’t aware of that.

“I have not seen your father’s record from the other physician, “the HMO’s urologist told me.

When my father did not respond to the hormonal therapy, and the pain in his spine became more intense, I insisted that he be given a new CAT Scan. The new CAT scan—which the HMO balked about doing—discovered a spot on his spine; in the exact location where my father was complaining about pain; the exact same spot where the HMO’s initial physician “gatekeeper”—who managed my father out of immediate care— told him he had “probably caught a draft.”

One week later, unable to breathe fully to clear his lungs because the pain in his back was now unbearable, my father was rushed to the hospital with pneumonia and placed in the ICU on a respirator.

During the first week of my father’s hospitalization, the cancer spread so rapidly into his spine he became paralyzed from the middle of his back down. The rapidly deteriorating condition of his lungs made a milogram and radiation therapy impossible—procedures which could have reduced the size of his spinal tumor had it been detected earlier. The HMO “gatekeeper’s” mismanagement of my father’s early care, coupled with a misdiagnosis by the HMO’s urologist, who initially wasn’t aware of my father’s patient record, his blood pressure levels, nor his PSA score, limited my father’s options for prolonging his life.

Four days before my father’s death, the attending physician at the HMO-owned hospital informed me that my father—whose mind and eyes were alert as he battled for each breath—was “terminal” and would not live out the week.

“You ought to give thought to taking your father off the respirator,” the HMO attending-physician told me, out of earshot from my father. “The corporation never intended for this equipment to be used this way.”

I stared at the man in the white coat, a garment considered almost sacred by my father.

“Doctor,” I said, staring directly at him, and speaking clearly and deliberately. “ I don’t care what the corporation intended. In my family, we consider life to be sacred, and we’ll do everything we can to preserve it.”

My father’s condition quickly worsened. He began to bleed internally, receiving 11 pints of blood over two days; his eyes turned from alert, to angry.

Unable to speak because of the tubes down his throat, my father signaled to me that he wanted to end his life. I tried to ignore what he was struggling to say. He pointed at the clock on the wall opposite his bed, and mouthed the words, “time to go,” I told him he was too ill to go home, and he shook his head in disgust. He pointed at all of the high-tech machines keeping him alive and turned his palms up as if to say, “what’s the use.”

I walked out of my father’s hospital room, found the HMO’s attending physician and asked him what death would be like for my father if we unplugged the respirator. His answer was flippant.

“I don’t know,” he snapped. “I’ve never experienced it.”

My questions, like my father, had become a burden for the corporation, which had mismanaged his care.

My father died the following day, refusing to breath into the respirator when the respirator technician instructed him to, taking that terrible decision off of the shoulders of those he loved.

My father never intended to continue living that way, as an extension of expensive machines designed to keep him alive, regardless of what inhumane reason “the corporation” gave for rationing their resources.

My father died with great dignity, on his own terms, while the healthcare “corporation” which mismanaged his care, killed the trust and confidence placed in them by patients and their families.

Thirty years later, that callousness, and the placing of profit-making over patient-mending, has brought the decades-deep rage against corporate medicine to a dangerous boil.